THE WRIGHT FAMILY

Born in 1722, Thomas Wright started work in a warehouse on London Bridge, created a hugely successful business, became Lord Mayor of London and built Bell House.

Bell House was built in 1767 for Thomas Wright, at a time when Dulwich was just starting to be built up: London was already the largest city in Europe and its buoyant economy was providing opportunities for many. Other Georgian houses were also being built in Dulwich Village, with The Laurels and The Hollies going up at the same time. Many of these Georgian houses survive but Bell House is one of the very finest.

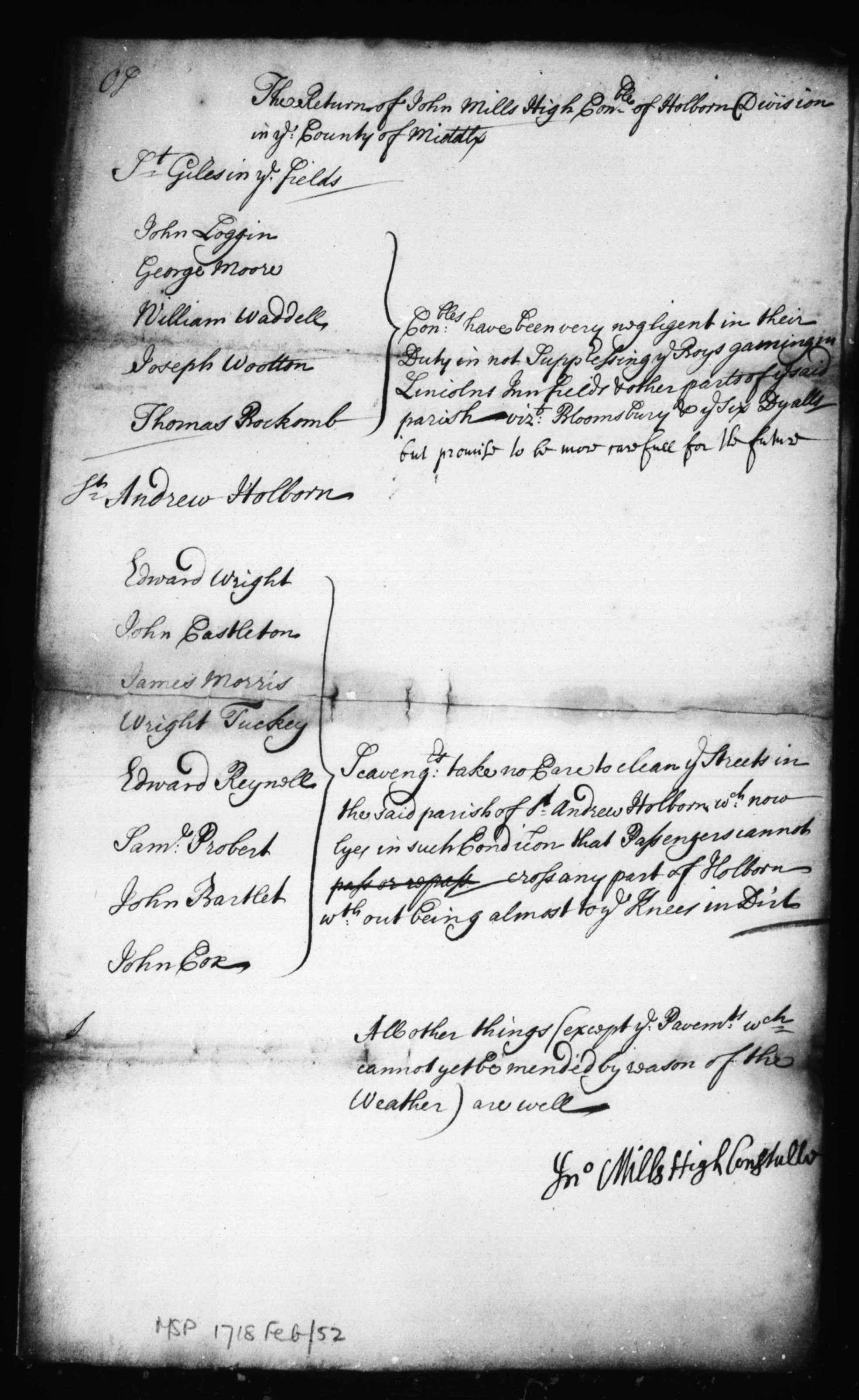

Thomas Wright was born on 26 April 1722 and christened at St Andrew, Holborn, a fine Wren church near his family’s home in Red-Lion Square. John Wesley preached at this church in 1737-8, when Thomas was in his teens. Thomas was the son of Edward Wright, a pastrycook and was also a scavenger, someone employed by the parish to oversee the ‘rakers’: men who swept the streets and carted away the rubbish. Street cleaning was a constant problem in Georgian London and in 1718, afew years before Thomas was born, Edward was indicted with other scavengers because they: ‘take no Care to clean ye Streets in the said parish of St Andrew Holborn wch: now lyes in such Condicon that Passengers cannot cross any part of Holborn without being almost to ye Knees in Dirt’.

Thomas’s father was from Aldington in Kent but moved to London and married Elizabeth Turvin at St Olave’s, Southwark in 1712. Edward and Elizabeth had a large family, at least eight children of whom five survived to adulthood and they lived in Red Lion Square, a smart, newly built suburb between Holborn and Bloomsbury. Edward died in 1726 when Thomas was just four years old.

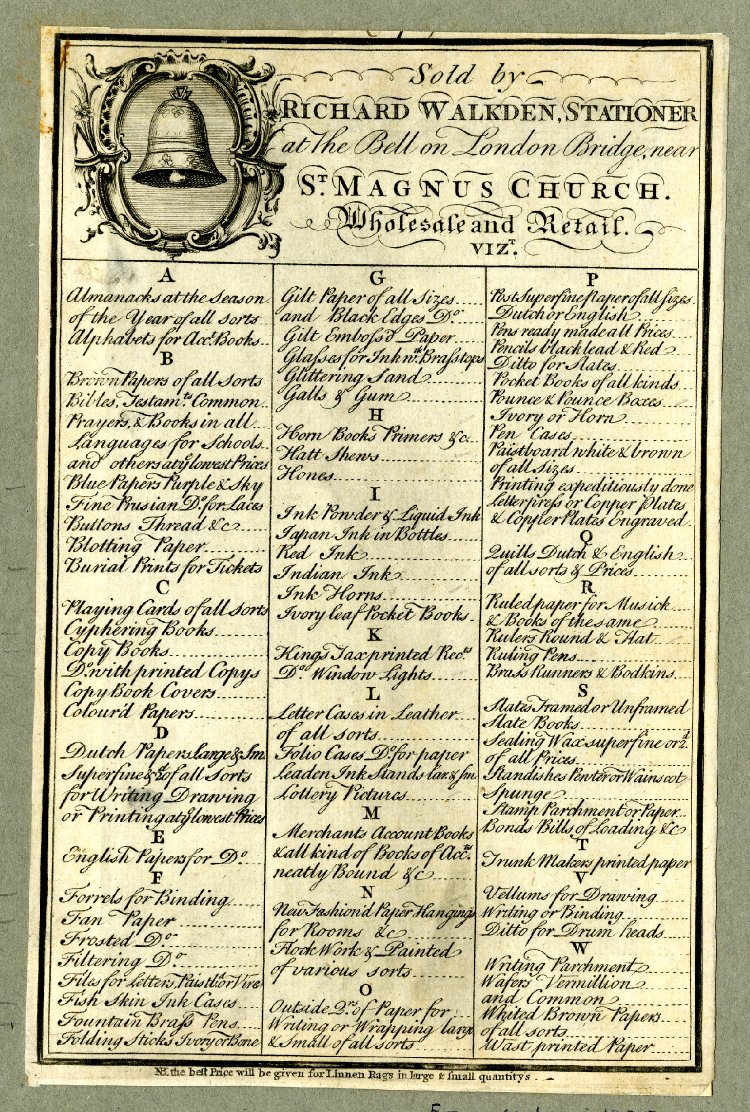

Thomas Wright started work in Walkden’s paper and ink warehouse ‘at the Bell on London Bridge, near St Magnus church’. At the beginning of the 18th century domestic and business servants and also apprentices had a close relationship with the family they served and they often all lived together in one social group, especially as merchants often lived ‘above the shop’. In 1738, on Thomas’s sixteenth birthday, his boss, Richard Walkden, citizen and stationer, made him an apprentice. We know Thomas must have been literate as, unlike printers, stationer apprentices had to be able to read. Thomas’s father had died 12 years earlier, he is described as deceased on the indenture, and a bond of £40 was paid to Walkden, who charged up to £100 for his apprenticeships: they were the route to a lucrative career. Walkden’s own father had died when he was young and he had been apprenticed to his mother, from whom he took over the family business. Stationers, together with booksellers, were the wealthiest members of the book trade due to the huge increase in printing and the foundations of the modern book trade were laid at this time with many firms such as Blackwells and Boosey & Hawkes still surviving today.

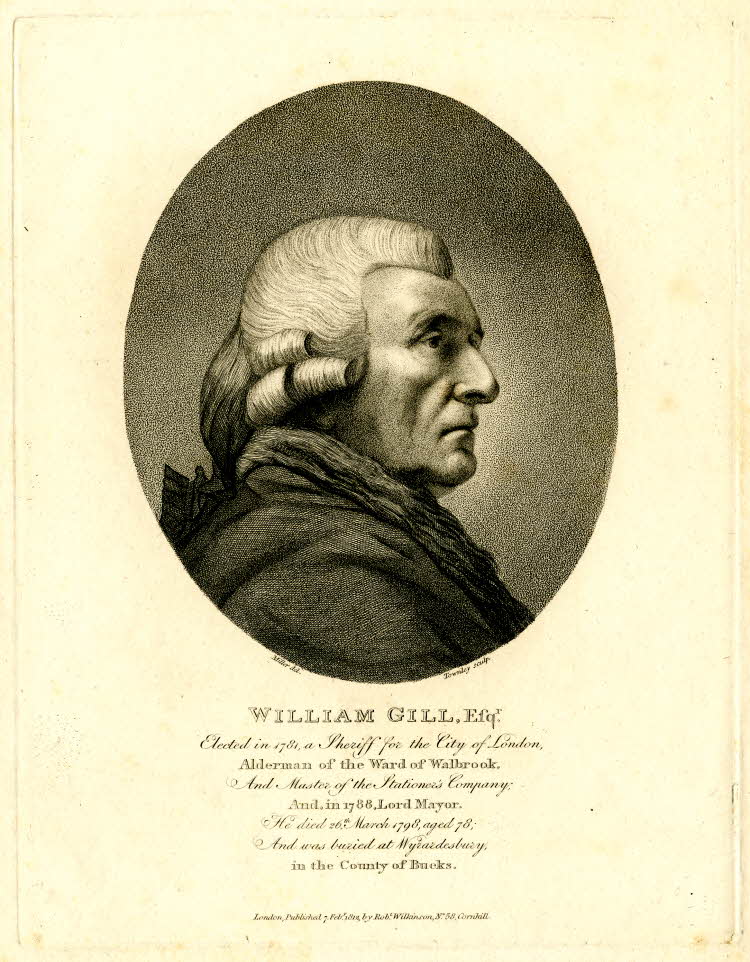

Thomas’s apprenticeship lasted for seven years, coinciding with war with Spain and Austria but by the time he had completed it in 1745, England was at peace. He then became a freeman of the City of London and was ‘clothed’ as a liveryman of the Stationers’ Company, meaning he had the right to wear their livery and to stand for office in the company. In 1746, Thomas married Ann Gill on 15 November 1746, at the church where his parents had married, St Olave’s, Southwark.

Like Thomas, Ann’s family was from Kent. Her grandmother, Susan Cox, was from Dartford and her grandfather George Gill, from Bexley. Her father, William, was born in Bexley and like Thomas’s father had moved to London where he married his wife, Elizabeth Lawrence, also at St Olave’s. One wonders whether the two families knew each other, or were even related, as they both originated in Kent and both had the surname Brooke as a first name in their family. Thomas’s grandmother was Mary Brooke and it was her brother James Brooke, Stationer and Sheriff of the City of London, to whom Ann’s brother William was apprenticed. Thomas went on to name one of his sons James Brooke, while Ann had a brother called Brooke, who died when she was 17 years old.

Thomas Wright’s father, Edward Wright, is described as both a pastry cook and a scavenger (road cleaner) but he also left Thomas £230 in his will so must have been wealthy. Pastry cook was a highly specialised trade that was much in demand. A guide to London in 1802 talks of ‘a pastry cook having been known to leave £100,000 to his heirs’ which shows it was not unknown for people to make large sums from what we would consider relatively mundane jobs. Rubbish collection too was a potential goldmine. Ashes and dung was sold to farmers but the real money was made by selling the dust to brickmakers. Thomas himself was described as a ‘warehouse worker’ in his lifetime though clearly he became a hugely successful, wealthy man. He mostly used the title ‘Alderman Wright’, rarely using ‘Thomas Wright Esq’. After his death, his son-in-law, John Willes, applied to the College of Arms for a coat of arms for the Wright family and in a book about the gentry in 1818 Thomas is linked to a long line of Wrights from Yorkshire but we have not been able to link him to this family. So Edward could have made a very good living, and similarly, Thomas could have started work in a warehouse with an understanding that he would take an apprenticeship from the master of the firm and thus get his feet on the first rung of the book trade ladder. Thomas does not appear in the registers of any London schools of the time, unlike his brother-in-law, William Gill, who was educated at the Merchant Taylors’ School. This does not mean he was uneducated of course, but he may not have been in that ‘middling sort’ strata which sent their sons to London schools like Merchant Taylors or Christs’ Hospital.

London was in a state of flux at this time with the genesis of a consumer society. For the first time people of the middling sort had extra wealth to spend and began buying in order to display their taste, wealth and gentility. This consumption would have included things like the china needed for the new fashion of tea drinking, clothes for different occasions and would also have included books to display learning and discernment. So printing and bookselling were very much up-and-coming businesses at the time, making the Stationers’ Company a good livery for an ambitious young man to join.

Wright & Gill on London Bridge

By 1748 Thomas Wright was a master stationer and in business with his brother-in-law, William Gill on the east side of the north end of London Bridge, in the old Chapel of St Thomas Becket which had been converted to secular use during the Reformation. It was close to the centre of the old 12th century London Bridge, with a lower chapel in the cellar at (or under) water level and an upper chapel at bridge level. Wright & Gill used the lower level as a paper warehouse and the upper level as a shop. They had a crane added to hoist supplies direct from the river and used the cellar as a paper store which surprisingly was reported to be ‘as safe and dry…as a garret’. Wright & Gill conducted business from these premises from 1751-59.

At this time London Bridge was the only bridge across the river Thames. With its narrow road due to the many buildings on it, and the animals being driven across to Smithfield, it was very busy. Traffic congestion led to a rule that people should drive on the left of the bridge to reduce collisions. This was incorporated into the 1835 Highways Act and in Britain we have driven on the left ever since. At the time Thomas was using the bridge there would still have been severed heads displayed on the south side. Between 1756 and 1760 the buildings on London Bridge were demolished or remodelled by George Dance and Sir Robert Taylor, both colleagues of Wright on the Court of Common Council. At one time Taylor was thought to be the architect of Bell House. So Wright & Gill had to relocate their business.

Wright & Gill moved to a ‘brick-built’ property at 30 Abchurch Lane on the north side of London Bridge. Brick-built was an important consideration after the Great Fire of London and indeed fires were reported twice in Abchurch Lane. Four houses were completely destroyed with Wright & Gill’s buildings ‘greatly damaged’ and only saved ‘with great difficulty’ in one fire. Four men died and another four were taken to St Thomas’ Hospital. Insurance records for the Abchurch Lane premises show that the property was insured for £500, later increased to £2,000, not surprising as paper was very expensive. Wright & Gill also had another warehouse at Walnut Tree Alley in Tooley Street which was insured for £300, a further property in Paternoster Row insured for £9,000 and property at an unspecified address insured for £7,000. In January 1770 Thomas Wright lost ‘over a thousand pounds worth of bibles and prayer books’ in a fire which consumed their ‘Oxford Warehouse’ in Paternoster Row.

Wright was closely involved in his livery company, the Stationers, and in 1777 he became its Master. The Stationers’ Company was unusual in that it acted both as a livery company and as a commercial entity in its own right: it owned the ‘English Stock’, a company which held the monopoly to print almanacs, psalters, catechisms and ABC books. This was extremely lucrative: the ‘Stock’ sold around 400,000 almanacs each year alone and these shares paid a dividend of 12.5% p.a., an exceptional return and more than twice the interest paid on government stock at the time. Thomas was able to leave his share of the English Stock to his wife in his will.

Wright & Gill, stationers

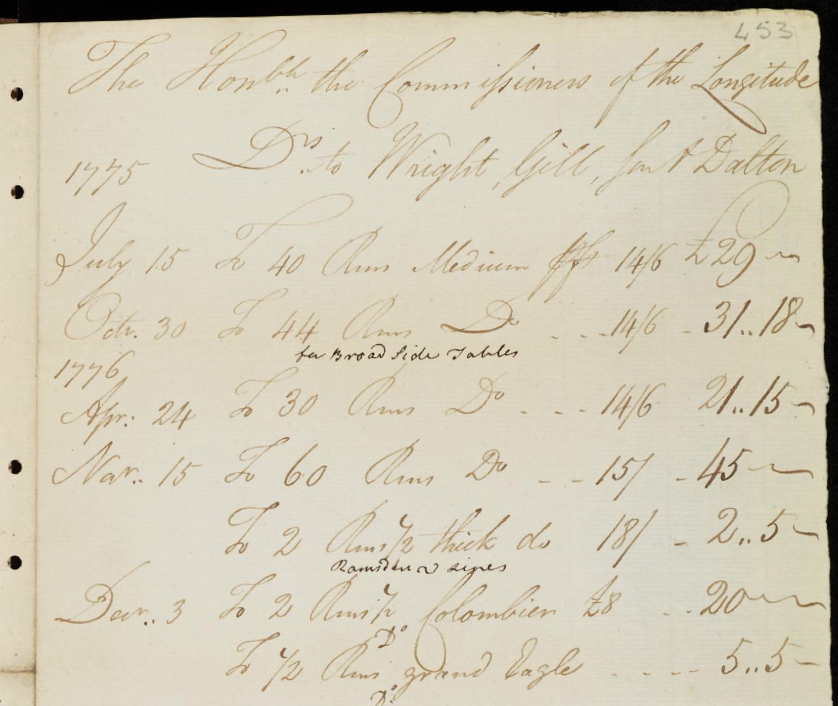

Wright and Gill’s initial success in business stemmed from selling paper. Among the organisations they supplied were Oxford University in the shape of the Clarendon Printing House, even after they stopped printing religious works, and also the Board of Longitude, the government body set up to discover a way of measuring longitude at sea. The Gill family had an interest in paper mills in Kent which would have contributed to their profit margin since they could access paper more cheaply than their competitors. William Gill had taken an apprenticeship in papermaking at Horton Mill in Wraysbury and later owned Sandling paper mill near Maidstone.

Wright & Gill also supplied the paper for the Royal Society. On 22 December 1791, the Society resolved to use Wright & Gill to supply the paper to print the Society’s transactions ‘750 copies be printed on large and 250 in small’. In January 1798 the Royal Society ordered the paper for the thirteenth volume of their Archaeologia, from Wright, Gill, and Dalton for thirty shillings a ream. The firm also supplied paper to hymn-writer, poet, editor and newspaper publisher James Montgomery (1771-1854). The firm’s success also came from printing almanacs, a highly profitable business, given they were bought by one in three of the population and were the second best-selling book after the bible.

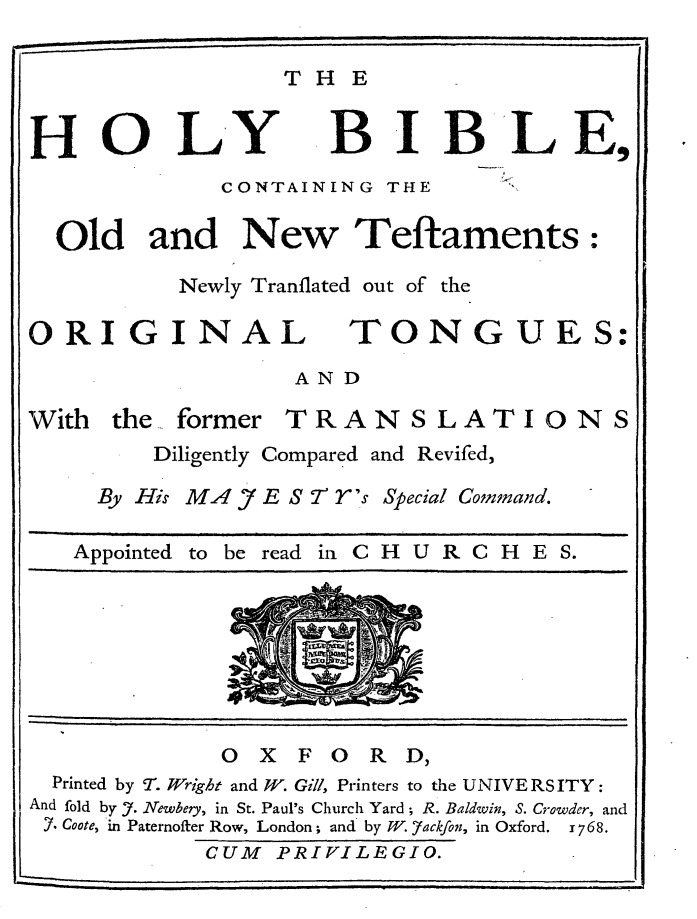

More financially rewarding still was the printing of bibles and prayer books, at that time owned by a cartel comprising the universities of Oxford and Cambridge, who then sold monopoly leases carrying the right to print books for both Britain and the lucrative American market. On Lady Day (25 March) 1765 Wright & Gill bought the right to print religious works for the University of Oxford, following a series of disputes between the university and their previous printers, the Baskett family. Oxford claimed Baskett produced books riddled with mistakes: one misprinted book was called the ‘vinegar bible’, because the parable of the vineyard was misprinted as the parable of the vinegar. Baskett employed ‘idle and drunken staff’ and things got so bad many Oxford colleges had to purchase their religious books from ‘Cambridge’ (their italics). Thomas Wright took charge of the negotiations, paid £850 p.a. for the lease and crucially agreed to indemnify the university against any law suits brought by the notoriously litigious Basketts. Oxford awarded Wright & Gill the lease for fourteen years and the amount paid was Oxford’s largest source of regular income at the time.

Wright & Gill were not printers so when they took control of Oxford’s Bible press on 28 January 1766, they subcontracted the work to local printer William Jackson. The books were printed on the ground floor of the Clarendon Building while Wright and Gill established ‘large and elegant’ apartments on the first floor above. Their 1769 bible, the King James Authorised Version, edited by Benjamin Blaney, became the standard Oxford text and is still printed today. Since Oxford held the ‘Bible Privilege’, that is the right to print the King James Authorised Version, Wright & Gill’s arrangement proved highly lucrative, especially as the Stationers Company, to protect their own monopoly of printing almanacs, agreed to pay them £550 p.a. to ‘forbear’ to print Oxford almanacs (Oxford also held the right to print them). Wright & Gill produced nearly a hundred different religious imprints and many of them survive which is unusual as they were very much ‘working copies’, used daily by families or religious institutions.

The bibles printed by Wright & Gill for Oxford University are one of the forerunners of modern typographical style in their simple format and sparing use of capital letters within the text. At the time many words were capitalised, including nouns, but these books ignored this custom and also used simplified spelling, making them look much more like modern imprints. The university also paid extra to have certain books within the bible starting on the right-hand pages and this resulted in extra white space, aesthetically pleasing but unusual for the time. Wright & Gill’s 1768 common prayer book was referred to at the time as ‘beautiful and correct’. Wright and Gill also supplied a good quality ‘thin Royal’ paper to the university for other uses.

Trade with America

In their 1778 lease renewal negotiations, Wright & Gill offered only £210 p.a. compared to the £850 they had paid for the first lease, telling the University that the contract’s value was hugely diminished for two reasons: firstly, because the Stationers’ Company had lost the monopoly to print almanacs, they were not prepared to make forbearance payments to Wright & Gill to stop them printing Oxford almanacs, nor were they inclined to help protect the bible press monopoly from unauthorised printers. Secondly, the Boston Tea Party and the outbreak of war with America had affected trade, and the colonists were now printing their own bibles in any case. There were no other competitors to force up the bid price and in fact Wright & Gill were the last holders of the lease, as the University took printing back in-house to what became the Oxford University Press. However, Wright & Gill continued to supply paper to the university press, including the paper to print five hundred copies of Julius Caesar.

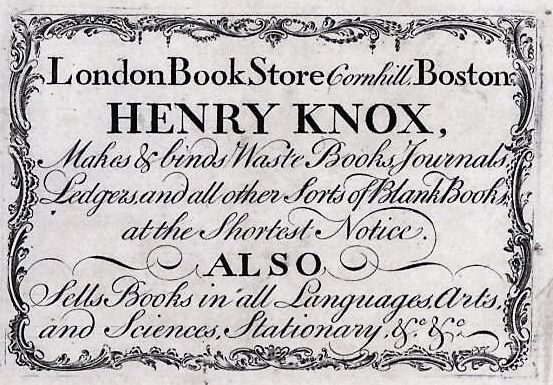

Thomas Wright was not averse to diversifying when the opportunity arose. When supplying books to America he was also happy to ship other client orders such as German flutes, bread-baskets and telescopes. The firm also sold into Quebec, Canada with a shipment leaving Deal in Kent on 28 March 1777. One such invoice to Henry Knox, the American revolutionary and first US Secretary of War, was for £656, over £42,000 today. Exporting to America had many potential difficulties. Ships could be delayed or lost; salt water and paper do not mix well and damp conditions on board often resulted in damaged or destroyed books. However, the rewards were potentially lucrative as prices were high and the colonies were to some extent a captive market as before Independence they were forbidden to print their own religious books and had to import them from Britain. Not surprisingly, Wright & Gill supported the king in the war and in 1778 gave £100 ‘to support the constitutional authority of Great Britain over her rebellious colonies in America’.,

Fraud

Wright & Gill became innocently and indirectly involved in a case of attempted fraud in 1755 when Thomas Wright gave evidence in the case of William Rutherford, aka Smith, aka Wherron. Rutherford had forged a badly written and misspelt note, purporting to be from William Wilmott and addressed to William Wallis, both stationers and business associates of Thomas. Rutherford wanted to be paid £21 but Thomas testified that the handwriting was not Wilmott’s:

‘I verily believe it not to be his writing. Mr. Wilmott spells his name with a double t, but this has but one t; and here are a great many mistakes in the spelling; but Mr. Wilmott understands accounts, and spells very well; but as to the writing, it is nothing at all like his writing’.

Rutherford was found guilty of intent to defraud and sentenced to death.

The Wrights move to Dulwich

After their marriage, Thomas and Ann set up home near the south side of London Bridge, close to Thomas’s business. They had a son called James Brooke, who died in infancy and a daughter, Ann, baptised 7 March 1751 at St Saviour’s, Southwark, now part of Southwark Cathedral. It is possible they had other children who did not survive infancy. Child mortality was high with a third of children not surviving to their second birthday while another third died before they reached their teens. The Wrights decided to move further south, joining the exodus of families from the bustle of the City which was fast becoming a place of business and manufacture rather than residency. The rapid improvement in roads and the construction of Westminster and Blackfriars bridges facilitated commuting and enabled Thomas to reach his business much more easily. Dulwich provided an attractive alternative, with its country air and spa at Dulwich Wells. The Wrights had their own coach but there was also a regular stage coach to Dulwich starting from the Pewter Platter pub in Gracechurch St, a stone’s throw from Wright & Gill’s office in Abchurch Lane, to the Crown and Greyhound, then two separate pubs in Dulwich Village. As the middling sort became more prosperous, wives were not required in the workplace and so began to stay at home, becoming what would be known in Victorian times as ‘the angel in the house’.

In 1766 Thomas Wright purchased John Ramsbottom's lease of what is now Bell House, which then consisted of a house, a three-acre field called Crutchmans, and two ancient cottages where Pickwick Cottage is now. In 1767 he replaced the existing house with one of his own. The College granted him a new lease at £5.10s. p.a., and a year later he was given permission to demolish the two ancient cottages in view of his having spent ‘a very considerable sum on his premises’. There was a Bell pub, just opposite the old College, roughly where the gates to Dulwich Park are now, which was demolished in 1792 but the bell which gives Bell House its name was installed in 1775, a little after the house was built. It is 17 inches in diameter (43cm) and weighs 1 cwt. It was cast by the Whitechapel Bell Foundry (also responsible for Big Ben and the Liberty Bell). In 1783 Thomas leased three meadows (12 acres) behind Bell House and also bought the use of the mill pond on Dulwich Common with the ‘right to take fish out...by angling and no other method’.

Having built Bell House and its accompanying coach house, the Wrights continued making improvements to their property, such as enclosing the waste ground in front of the ha-ha (most of these ‘wastes’ belong to the Dulwich Estate but unusually Bell House owns its own) and planting trees. A tributary of the River Effra runs from the pond further along College Road down to the Village. It is now under the grass verges but the ha-ha still sometimes collects water from this ancient river. On the site of the ‘two ancient cottages’ he built two new ones, now incorporated into Pickwick Cottage. Bell House would have been heated by wood but in the 1750s coal began to replace firewood. One of the cellar windows (to the left of the front door) was replaced by a coal chute at some point.

A community-minded man

The Wrights played a role in the local Dulwich community. Other members of the family lived in Dulwich, for example their nephew Francis Gill and his wife Jane lived at Pond House and another Gill relation was the daughter-in-law of Henry William Atkinson, Moneyer, who lived on Dulwich Common from 1783 to 1798 and was responsible, until the Royal Mint was nationalised in the 1840s, for the manufacture of the nation's coinage. Thomas’s business partner was also his brother-in-law and they seem to be a close family, certainly Thomas remembered many relatives in his will.

The Wrights were sociable and entertained often. Richard Randall, the Christ’s Chapel’s organist and a popular guest in Dulwich society, often mentions the Wrights in his diaries. Randall gave Mrs Wright music lessons and for more than twenty years he was invited to Bell House for meals from breakfast through to supper and he also joined the Wrights on theatre trips and other outings. In 1772 Wright co-founded (with John Willes, his friend and future son-in-law) the Dulwich Quarterly Meeting of residents, which turned into a regular dining club at the Greyhound pub called the Dulwich Club. In 1791 he supplied the Minute Book, in which the two stewards at each feast and the attendees were recorded. This club was widely involved in Dulwich life. In February 1798 the club held a meeting with the Dulwich College Master to receive contributions for the defence of the country and in May the same year they met with the College Warden to form the Camberwell Association: an armed association which operated until the Peace of Amiens in 1802.

In the eighteenth century there was little organised support of the poor beyond the Elizabethan poor laws but there was a definite Enlightenment trend to provide for those less well-off, though often with the aim of warding off unrest or revolution. Nevertheless, much-needed new resources were available as individuals supported new charities. It was very much up to each person how much they gave and how often and the Wrights were generous; they donated on a regular and sustained basis while also making one-off donations. In addition Thomas Wright gave many institutions the benefit of his business expertise.

In Dulwich their charity was on an ad hoc basis. In 1799 Ann Wright gave £10 for the relief of relatives of soldiers wounded during ‘our war with Holland’. Thomas supported local charities, presented a bible to the Chapel in 1782, and helped to secure a fire engine and a house ‘south of the Pound’ in which to keep it. For a hundred years the bells of the Chapel and Bell House were rung whenever a fire broke out in the Village. Thomas Morris described how, when a fire broke out at the bakers on Bonfire Night in around 1847, the ‘Fire Bell’ on top of Bell House was rung with all its might.

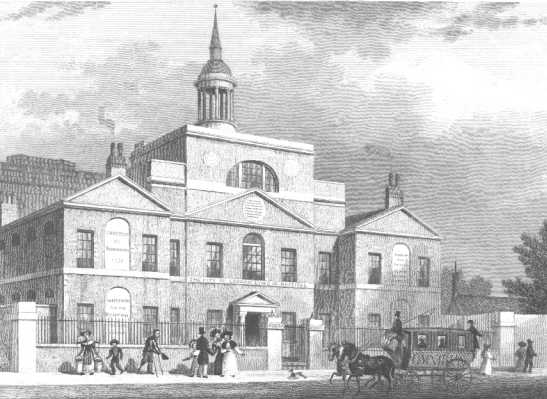

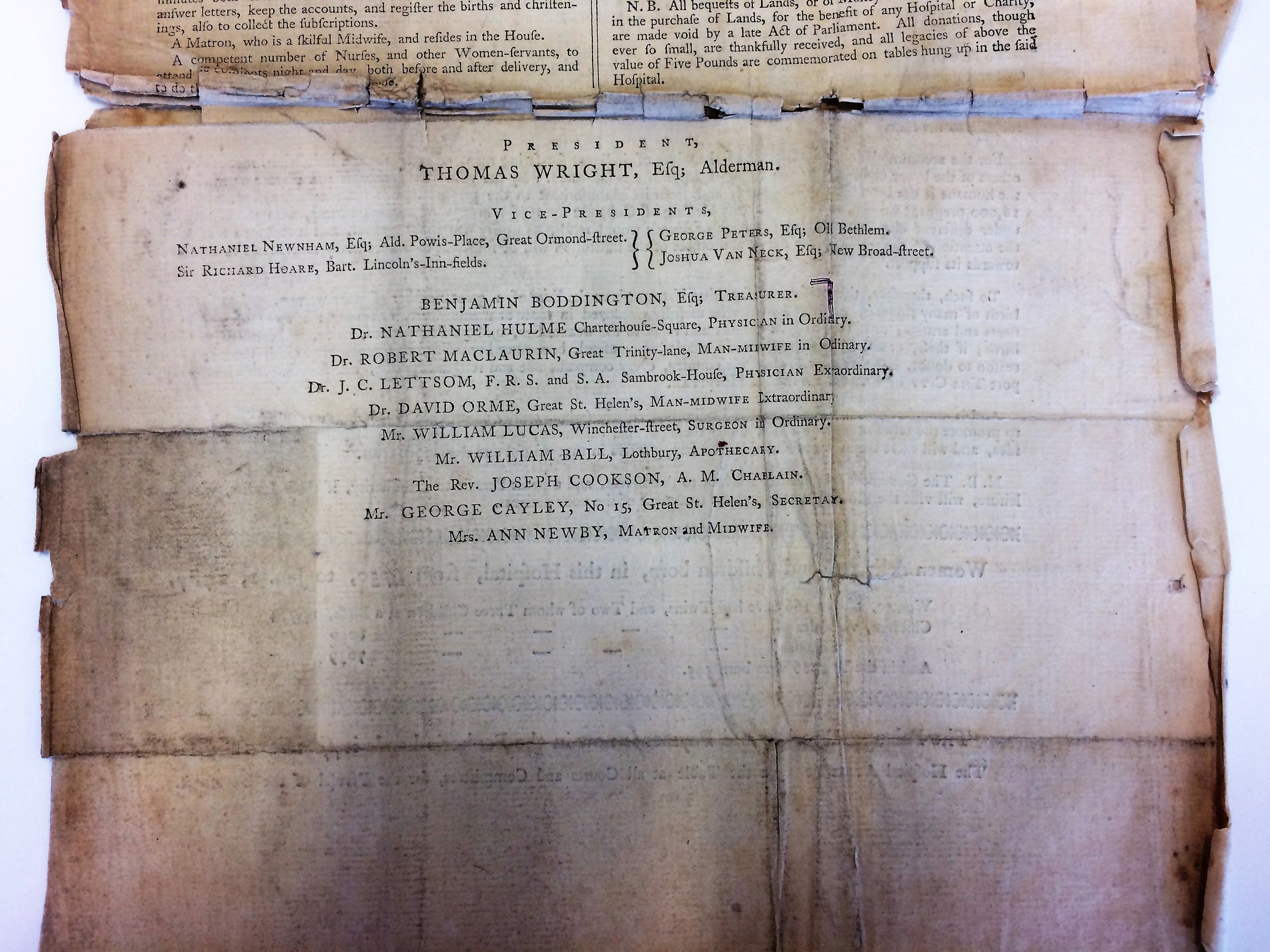

Wright was also involved in charitable endeavours across London as well as giving his time as a justice of the peace. With his business partner and brother-in-law William Gill, he was active in many London hospital charities which provided for the poor of London. He was a governor of St Thomas’s Hospital, vice-president of both the Middlesex Dispensary and the City Dispensary, clinics set up to bring health care to the working poor, but the hospital he was most involved in was the City of London Lying-in Hospital, one of the first maternity hospitals in London. Thomas first became involved with ‘this humane and useful institution’, which provided maternity services for the wives of poor tradesmen, in the 1770s and with William Gill he would attend the Sunday baptisms of babies born in the hospital, make donations and attend governor meetings where they would hire staff, approve bills and deal with the many women applying for admittance, always more than they could accommodate. Charity in the eighteenth century was often moralistic and single women would not be admitted until 1912. Each governor had the right to nominate patients but all patients had to prove they were married, were deserving of charity and agree to their new-born being baptised in the hospital chapel.

The weekly governor meetings were held at local coffee houses until a purpose-built hospital was erected near Old Street roundabout and each week about a dozen new mothers would be brought before the board (or Court as it was known) to ‘return thanks’ for the benevolence they had been shown. Other mothers were summoned to be admonished for their bad conduct while staying at the hospital. There is no record of what this bad conduct entailed but the rules for patients were very strict and they were inpatients for a long time, at least six weeks according to the regulations, though this must often have been shortened as most families would not have been able to do without a mother for so long. From four days after delivery the women needed matron’s permission to lie down on their beds and from three weeks after giving birth they were expected to sew needlework for the hospital. Labouring was done in the ward that expectant and newly-delivered mothers shared: a separate room for labour was vetoed in case the patients suspected experiments might be performed on them.

Mortality at all hospitals was high due to a lack of hygiene. ‘Childbed fever’ as post-partum infections were known, was usually caused by the doctors themselves and during the time Thomas was involved the hospital had to be closed temporarily due to rampant infection, which must have been difficult as there was such a need for the hospital’s services. It would not be until the 1850s that simple precautions like handwashing would bring down the numbers of post-natal deaths. Vermin such as bedbugs were a constant issue, as was alcohol abuse, and as president Thomas banned the drinking of porter in the hospital due to its ‘evil effects’. Other issues he ruled on included the lack of lighting at night: his solution of one candle per ward per night is surprising as it must still have been very dark. He also stopped the long-term practice of patients having to buy tea and sugar for the nurses; he raised the nurses’ wages so that they could buy their own. Thomas was a generous benefactor. At a time when most people were donating around £5, his usual donation of £20 can be seen in the benefactor lists again and again. Both he and William Gill were later presented with ‘staffs’, a sign of devoted service to the hospital.

At the same time Thomas was president of the hospital one of its senior physicians was Dr Lettsom of Camberwell. It is tempting to suppose they were friends, given their involvement here and that they were both active in public dispensaries. In addition they both lived in south-east London at a time when there were far fewer houses in this area. Dr Lettsom was involved with the hospital for many years, was also a philanthropist and also supported the abolition of the slave trade.

The London Asylum for the Deaf and Dumb

Thomas Wright was a benefactor of the first free school for deaf children in Britain. Until it opened in 1792, poor British deaf children had no formal education as the only school for the deaf in the whole of Europe was in Paris. Edinburgh and London had private schools but only for those who could afford to pay. The Asylum for Deaf and Dumb Poor Children was founded by two friends: Rev. John Townsend and Rev. Henry Cox Mason, vicars in Bermondsey. Together with Henry Thornton, a philanthropist, and Mrs Creasy, one of Townsend’s parishioners whose deaf son, John, had benefitted from a private deaf academy, the money was raised to set up an asylum near Tower Bridge. Within six months the team had found premises, hired a headmaster and registered their first pupils. The school was popular with parents of deaf children and also with benefactors and grew quickly. Children learnt to read, write and do arithmetic and there were morning and evening prayers and two church services on Sunday. Classes ran seven days a week with scripture studied on Sundays; holidays were restricted to a fortnight at Christmas, later extended to a fortnight in the summer. A letter in The Gentleman’s Magazine of 1795 tells how the children were taught to be useful to themselves, a comfort to their friends and learn ‘what might be valuable to them both here and in the hereafter’.

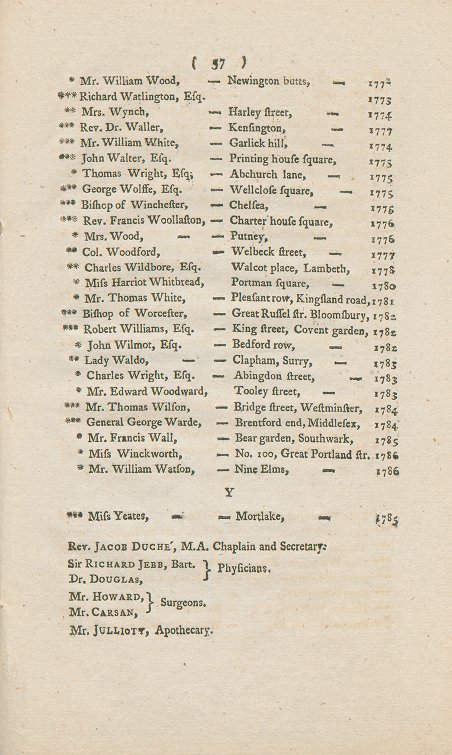

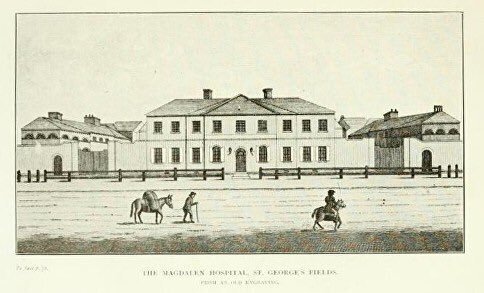

Thomas gave his money, his time and his business expertise to many other charitable organisations of which the following are examples. The Marine Society was formed in 1756 to take in poor boys and prepare them for a life at sea, thus solving the need for a constant supply of sailors with the issue of young men roaming the streets. He donated to the Candlewick Ward School (now part of Sir John Cass School) and the Magdalen Hospital for the Reception and Training of Penitent Prostitutes. He also supported the Philanthropic Society which aimed to ‘rescue from destruction the offspring of the vicious and dishonest’. In the 18th century responsibility for deserted and vagrant children lay with the parish where they were found, provided no other place of settlement could be discovered but this obligation appears to have been widely ignored. The Philanthropic Society was founded in 1788 to protect and reform both the offspring of convicted felons and children who had themselves broken the law. The boys were taught printing, bookbinding, shoe making, tailoring, rope making and twine spinning and it is tempting to think Thomas Wright was involved in the printing or book-binding lessons. The girls were trained to be "menial servants"; they made their own clothing, shirts for the boys, and washed and mended.

Many of these organisations were based in an area called St George’s Fields in Southwark, a kind of charitable campus. Two of the largest were Bridewell Prison and Hospital which punished the disorderly poor and housed homeless children, and Bethlem, the mental asylum known for selling tickets to view the inmates, and which gives us the word Bedlam. These two organisations were governed jointly and, because it was prestigious to be a governor here, there were large numbers of them (270 in 1700). However, only a small number of governors were actively involved and Thomas was one: ‘Thomas Wright, Alderman’ appears on many of the minutes. His brother-in-law, William Gill, was also a governor, as was their business partner, Richard Dalton. The homeless boys were taught to read and write and were then apprenticed to trades including weaving, shoemaking and glove making. As both a hospital and a prison, Bridewell provided quite advanced medical care for the time with a surgeon, physician, regular inspections, baths, and clean straw bedding and laundry to prevent infection. It’s possible that the poor used Bridewell as a means of accessing medical care. In 1789 the prison reformer John Howard said of Bridewell:

Each sex has a workroom and a night-room. They lie in boxes, with a little straw, on the floor…. There are many excellent regulations in this establishment. The prisoners have a liberal allowance, suitable employment, and some proper instruction; but the visitor laments that they are not more separated . . . no other prison in London has any straw or bedding.

Thomas donated to the Humane Society and was made a governor for life. Originally called the Society for the Recovery of Persons Apparently Drowned, it was founded by two doctors in a City coffee house because they were concerned about the number of people being taken for dead and even buried alive. Their aim was to train people in resuscitation techniques to rescue the many people who drowned in the Thames at a time when few people were taught to swim. The Society paid 4 guineas to the rescuer and 1 guinea to anyone who allowed the resuscitation to take place on their property, leading to a widespread fraud whereby two people would share the proceeds when one of them pretended to have drowned while the other pretended to have rescued him.

In 1780 he joined the Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge (SPCK) which at that time was mostly engaged in starting charity schools. He was also a member of the Patrons of the Anniversary of the Charity Schools from 1778 – 1798, an umbrella organisation for benefactors of charity schools. They met at the Queen’s Arms Tavern in Newgate St and organised an annual service at St Paul’s where they collected donations for the schools of which they were treasurers or trustees.

The Asylum for Orphan Girls

From 1775 onwards, Thomas was also a generous benefactor of this organisation, and paid them an annual sum of at least three guineas; he also left them £100 in his will. In 1758 John Fielding, a London magistrate, social reformer and brother of the author Henry Fielding, wrote of girls deserted on the streets of London and his fear that they would be forced into a life of prostitution. Just as the Magdalen was founded to reclaim prostitutes, the asylum aimed to prevent girls falling into prostitution in the first place. Fielding gathered wealthy patrons to fund a ‘reformatory’ to take in these abandoned girls, raise them ‘free from the prejudices of evil habits’ and train them to work as domestic servants. The rules for entry were tough: as well as being an orphan, only girls between the ages of nine and twelve were admitted and they must be free from disease or deformity; non-white girls were also denied entry. Once admitted, the orphans helped pay for their keep by making clothes which were then sold. These rules seem harsh to us but in a society preoccupied with moral issues charitable activity had to go hand-in-hand with a moral commitment from the beneficiary. Donors like Thomas were motivated by civic spirit and Christian morality.

Thomas Wright’s charity extended further than just London. In 1762 Jean Calas, a Huguenot cloth merchant in Toulouse was found guilty of the murder of his son. He was publicly broken on a wheel, strangled then burnt to ashes. Voltaire took up the case and argued that anti-Huguenot hysteria had influenced the verdict; he also set up a fund for Cals’ wife and family. Wright and Gill contributed to both the fund and Voltaire’s campaign and may have facilitated the pamphlets Voltaire circulated in London, either by supplying the paper or printing. In 1765 the conviction was reversed.

Theft at Bell House

On Saturday 2 December 1769, the Wrights were the victim of theft in their new house at Dulwich, discovered by their coachman, Rubon Cannicot, aged 32, who lived in the coach house with his wife of one year, Hannah. James Simpson was accused of stealing a woollen cloth coat, value twenty shillings, belonging to Thomas Wright. Rubon Cannicot gave evidence at the Old Bailey:

‘I am coachman to Thomas Wright; he lives at Dulwich; our coach was locked up, and the great coat on the coach box. The key was left in the door, on the outside; the yard gate was all fast, and the yard is walled all round; whoever got the coat must get over the wall. I know nothing of the prisoner, I never saw him to my knowledge before I saw him here at the bar; the coat was missing last Saturday morning’.

Simpson took the coat to Cheapside and offered it to Hugh Riley, a dealer in old clothes and rags. As well as being a clothes dealer, Riley was also a member of the City of London’s police force and seems to have been suspicious of Simpson. Riley and Simpson went to Paternoster Row, to a little court that leads to St Paul's churchyard, where Riley offered Simpson fourteen shillings for the coat but would not pay ‘till he sent for a surety’ (meaning someone who could vouch that the coat was Simpson’s to sell). The coat was advertised, and Rubon Cannicot described it to the lord mayor ‘before he saw it’. The prisoner’s defence was as follows:

‘My brother was a coachman; I had this coat of him; he was coachman to Mr Hutchinson in Southampton. I offered it to this man; (I) am bricklayer; my brother has been dead some time; I am a Guernsey man’.

The verdict was guilty and the sentence was transportation to the American colonies. Mortality to the American colonies was fairly low (at least compared to the later transportations to Australia) due to the economic value of the prisoners; on arrival they would be indentured for around £10 for the length of their sentence, at which time they were free. Some even returned to England though this became harder to do after the War of Independence. When the war commenced Britain began transporting prisoners to Australia instead.

At the time the Dulwich stocks bore the motto: 'It is the sport of a fool to do mischief, to thine own wickedness shall correct thee' and never has a quotation been more true. Simpson must have reflected on his bad luck on that day in 1769, when he stole a coat from a village five or so miles distant from London and then tried to sell it in Paternoster Row, the one place the livery would be readily recognised, the place where London's booksellers and stationers were based, just a stone’s throw from Stationers' Hall in Ave Maria Lane where Thomas Wright made almost daily journeys. Simpson's further misfortune was to try to sell the coat to someone who, before there was an organised national police force, turned out to be an off-duty member of the City's own law enforcement body.

Thomas Wright’s involvement in the City of London

Thomas Wright took a diligent role in civic affairs in the City of London from 1764 onwards. At this time the City was developing rapidly and confidently. The Seven Years War had just ended, paving the way for Britain’s global expansion. In 1761 the City’s medieval gates were demolished in an act of symbolic and practical modernisation. Sewers and water mains were laid, streets were paved or cobbled. In 1764 Thomas became a member of the Court of Common Council, the City of London’s council, for Candlewick ward, where his business was situated.

In his ward Thomas was responsible for the collection of the coal duty tax, originally levied to support children orphaned by the Great Fire of London but by then used for other municipal obligations such as paving the streets, by 1773 the City had paved from Temple Bar to Aldgate. Thomas was made a sheriff in 1779 and crowned his public service in November 1785 by becoming Lord Mayor of London. The following is an account of his installation as Sheriff:

Yesterday morning the two new Sheriffs, viz. Aldermen Wright and Pugh, went in their carriages to Stationers’ Hall, where they breakfasted, and afterwards proceeded with the Master, wardens and Court of assistants of the said Company to Guildhall, where they were sworn into their offices, with the usual formalities. Their chariots were very elegant. The livery of Alderman Wright is a superfine orange-coloured cloth, richly trimmed with silver; Alderman Pugh's is a superfine green cloth, with a rich broad gold lace, and both make a grand appearance as any Sheriffs have for several years. The old and new Sheriffs returned from the Hall to the Paul's-Head Tavern, Cateaton Street when, according of annual custom, the keys of the different jails were delivered to the new Sheriffs, and they were regaled with walnuts and sack by the Keeper of Newgate. After the ceremony at Guildhall, the Sheriffs etc. returned to Stationers’ Hall where an elegant dinner was provided by Mr. Sheriff Wright. The whole was conducted with the utmost propriety, and was the better attended than any feast given on a similar occasion, there being sixteen Aldermen present besides the Sheriffs. A Correspondent has favoured us with the following description of the painting on the new Sheriff's chariot: Mr. Alderman Wright's - 'Liberty, in a fitting posture, with her rod in one hand, and her other on the Roman faces, while a little-winged Genius is presenting her with a code of laws.'.

Lord Mayor of London

Thomas Wright’s Lord Mayor’s Show in November 1785 was particularly splendid; the twelve guildsmen of the Stationers’ Company insisted on accompanying the procession in their own coaches, instead of on foot (the previous practice). The coach Thomas used was the one used by the Lord Mayor to this day. It transported him to the waterside where he stepped into the City Barge which was accompanied by all the livery company barges blazing with streamers and pendants. The barge took him to Westminster where he took his oath before returning by barge to Blackfriars and then back in the coach to the Guildhall for ‘a magnificent entertainment’. Thomas’s coachman at this time was Thomas Berry. Berry remained the Wright’s coachman until the alderman’s death in 1798. He then remained in Dulwich but became a plumber. Berry’s three daughters went on to run a school at Old Blew House on Dulwich Common. During his mayoralty he was granted full use of the Stationers’ Hall and its plate. He had a banner made of his arms for use by the Stationers.

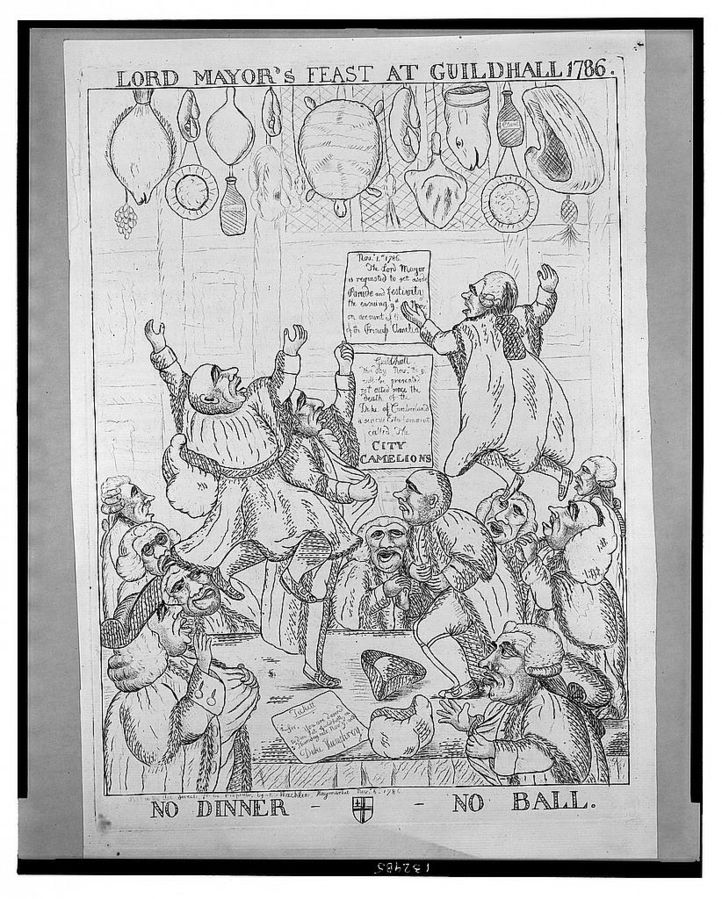

Towards the end of Thomas’s mayoral tenure, in October 1786, George II’s daughter, Princess Amelia, died and the country went into mourning. The Lord Chamberlain proclaimed that for Lord Mayor’s Day the next month, no liverymen should ‘walk or stand in the street, or pass in their barges on the water’. The artillery company should not march or fire their guns. There should be no ringing of bells or ‘other outward show of rejoicing’ such as a feast. A contemporary print shows Thomas’s colleagues not at all happy with the lack of festivities. In 1786 on the conclusion of his mayoralty Thomas presented the Stationers’ Company with a large silver tea urn.

Apprentices

During his time as a master stationer Thomas Wright took on many young apprentices for varying sums ranging from £20 for Thomas Jones in 1769 to £600 in the case of Thomas Kirk in 1765. His partner, William Gill, seems to have taken on only two apprentices. One was his own son, Robert, and in 1769 he apprenticed Roger Pettiward for £1,050. While high apprentice premiums were not unknown (Daniel Defoe talks of Levant merchants charging £1,000 in the 1720s) most apprenticeships were bought for much less. These large amounts must surely reflect the success of Wright & Gill’s business and the benefits that would accrue to anyone connected with it. Indeed after his apprenticeship Roger Pettiward became a ‘partner in the respectable firm of Wright & Gill’ and was wealthy enough to rebuild Finborough Hall in Suffolk.

Wright & Gill took on a young employee, Richard Dalton, who had come to London from Wigton, Cumberland and later made him a partner in the company. Dalton lived at Camberwell Green, not far from Dulwich. Thomas and Richard became great friends and Dalton was an executor of Thomas’s will. Wright & Gill was a very successful company and Thomas made such a fortune that it attracted the notice of the press, though he himself had a reputation for ‘great application and frugality’. Newspaper cuttings from 1785, the year he became mayor, talk of his:

‘property in the 3 per cents, to the amount of near £180,000. The very interest of this sum exceeds the Prince of Wales actual income! And independent of it, Mr. Wright's profits in his trade, as a stationer, are supposed to be very little short of it!’

Thomas Wright died suddenly on 8 April 1798, during a walk in the garden at Bell House. He had an epileptic fit and medical help could not be summoned in time. He was 76 years old and was described as a ‘truly humble and pious Christian, a faithful and affectionate husband, a most tender and indulgent father, a sincere and generous friend, a very good and kind master and a worthy and benevolent member of society’. He specified in his will that he was to be ‘buried without much expense’. William Gill, his close friend, brother-in-law and business partner for over fifty years had died just two weeks before him. It was said that they never had a dispute or an angry word during their long and prosperous lives.

Thomas’s wife Ann died in 1809. All three, together with Ann and William’s sister, Elizabeth Kincaid, are buried at St Andrew’s, Wyrardisbury (now Wraysbury) Church, in Buckinghamshire where the Gills had lived. Thomas left a fortune of £400,000, the bulk of which went to his wife and daughter. His will was proved on 21 April 1798 and in it he says:

‘I give to the masters and keepers or wardens and commonalty of the mystery or art of a stationer of the city of London two thousand pounds, four per cent bank annuities upon trust to pay apply and distribute the yearly dividends and yearly produce thereof upon the first day of January in each year or as soon after as may be, in manner following, that is to say ‘the sum of fifty pounds eight shillings, part of such dividends, unto and amongst twenty four poor freemen of the said company, not receiving any other pension from the company, in equal shares and proportions at two pounds two shillings each’. To the clerk of the said company for time being the sum of three pounds three shillings, other part of such dividends, for his trouble upon this occasion. And the sum of twenty-six pounds nine shillings, residue of such dividends, in and towards the providing and defraying expense of a dinner for the master, wardens and assistants of the said company upon the day of such distribution’.

He also left £500 to the Lying-In Hospital. When this legacy was announced at the governor’s meeting the board voted to make Thomas’s wife and daughter both honorary governors of the hospital for life and his name was painted on a panel in the chapel. He also left £100 to the poor of Wraysbury parish. He gave the Stationers’ Company £2,000 to distribute the income from it to 24 poor freemen and similarly gave £105 to divide among 20 poor households in Dulwich.

Wright & Gill continued after the death of the founding partners and included Gill’s son, their favoured apprentice Richard Dalton and four brothers named Key who had bought into the firm after Thomas’s death.

Thomas’s daughter Ann inherited everything and in 1811 a new lease of the Bell House property was granted to her at the increased rent of £128 p.a., with the right to channel water from the mill pond ‘through the pipe or plug already in the same’ into her own ponds although the College now took over responsibility for maintenance. The staircase at Bell House may have been replaced this time so perhaps Ann took the opportunity to update the house when she inherited. Ann married very late in life, on 27 March 1813, at the age of 64, four years after her mother died. She married John Willes, the owner of Belair House, Gallery Road, at St Mary’s Lambeth. Willes had already had the luck to marry another heiress, Rachel Wilcocks, niece of the Bishop of Rochester, and was himself 78 years old when he married Ann. He was a close family friend who had been the executor to Ann’s mother’s will. He may have known Thomas Wright through his career as a corn factor, as in 1762 Thomas had paid £2,500 for the office of corn meter, giving him the duty paid for the official measuring of corn. Willes was also on the board of the Lying-In Hospital when Thomas was President. Ann and John Willes did not live long to enjoy their joint fortunes; Ann died on 27 October 1817, aged 68 and is buried with her parents in Wraysbury. John died in 1818 and has a large tomb in the burial ground in Dulwich. Thomas Wright’s sister, Mary, had married Nicholas Trice and had a 17 year old grandson called Thomas Trice. Ann Wright Willes left all her property to Thomas Trice, subject to a life interest in favour of her husband John Willes. It was a condition of the bequest to Thomas Trice that he change his name to Wright, which he duly did. On 8 June 1818 the Prince Regent granted John Willes, on behalf of Thomas Trice, ‘now a minor’, the use of the surname and the arms of Thomas Wright in lieu of his present surname and arms, in compliance with the last will of Ann Wright Willes. John Willes died in August 1818 and in 1820, still technically 'an infant' aged 20 (his guardian Mrs Elizabeth Dennis Denyer, who was John Willes’ executor, had to be with him at the ceremony), Thomas Trice fulfilled the request of Ann’s will and became Thomas Wright. The Dulwich property Ann inherited included everything from Oakfield on Dulwich Common to what is now the College gates to Dulwich Park. She also inherited Ilderlsy Grove and a large acreage centred on the shops at West Dulwich, including the odd numbers of Park Hall Road, though this was as-yet undeveloped. Thomas Trice Wright married Cordelia Willes, John Willes’ niece and they had two daughters, Cordelia (who married the Rev George Martin Bullock) and Ann. In 1827 Thomas Trice Wright asked for a new lease of Bell House, which he said had been occupied by his relatives for a very long time. He was granted the new lease, but with Bell Cottages (now Pickwick Cottage) excluded. In 1847 Cordelia died and two years later Thomas married Sophia Reeves. They had no children and lived in The Grange, Chalfont St Peter, Bucks. The 1854 Terrier named Thomas Trice Wright as tenant of Oakfield. In 1877 Thomas Trice Wright died. His executors sold Oakfield, then occupied by Joseph Harris, to Robert Palmer Tebb, of 83 Lombard Street, London, for £4,500.

Thomas Wright. Source: Stationers' Hall

Thomas Wright’s apprenticeship indenture

Thomas was apprenticed at Walkden's warehouse

Anne Wright

Thomas’s father, Edward Wright, being censured for not keeping the roads clean. Source: London Lives

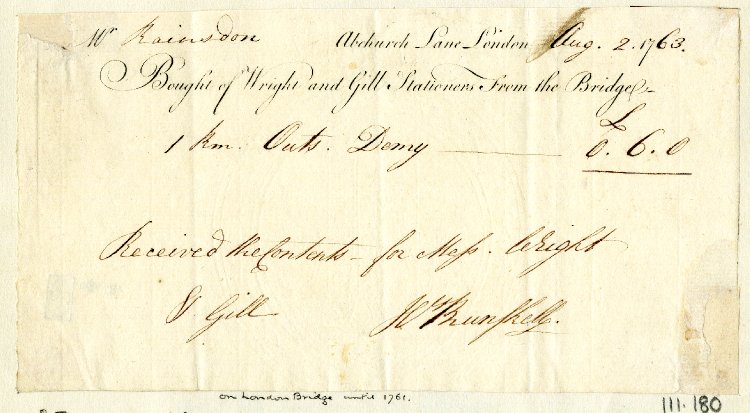

Wright & Gill letterhead 'from the Bridge'. Source: Bodleian Library

London Bridge in Thomas Wright’s day

Part of a Wright & Gill bill to the Board of Longitude

Almanac of the kind printed by Wright & Gill. Source LMA

1794 almanac showing the ‘Powder Plot’ on 5 November

Almanac showing Thomas Wright as Sheriff

Bible printed by Wright & Gill. Source Bodleian Library

Thomas Wright supplied stationery to Henry Knox in Boston

Wright & Gill book of common prayer printed in the year he built Bell House. Source: Bodleian Library

Wright & Gill in a contemporary biography collection

Thomas Wright was President of the City of London Lying-In Hospital

Thomas Wright was on the hospital board at the same time as the celebrated Dr Lettsom

Thomas Wright's name in a list of benefactors of the asylum for orphan girls

Minutes for Bridewell & Bethlem. Thomas Wright's name is on the left-hand side.

Magdalen Hospital, where Thomas Wright was a benefactor

William Gill, Thomas Wright's business partner and brother-in-law for over 50 years

Guildhall, 1782. Thomas Wright is front-centre, with his back to us, looking over his shoulder. Source: Collage

Common Council chamber, Guildhall. Source Bishopsgate Institute

Response to Thomas Wright’s ban on celebrating the Lord Mayor’s Show. Source: Library of Congress

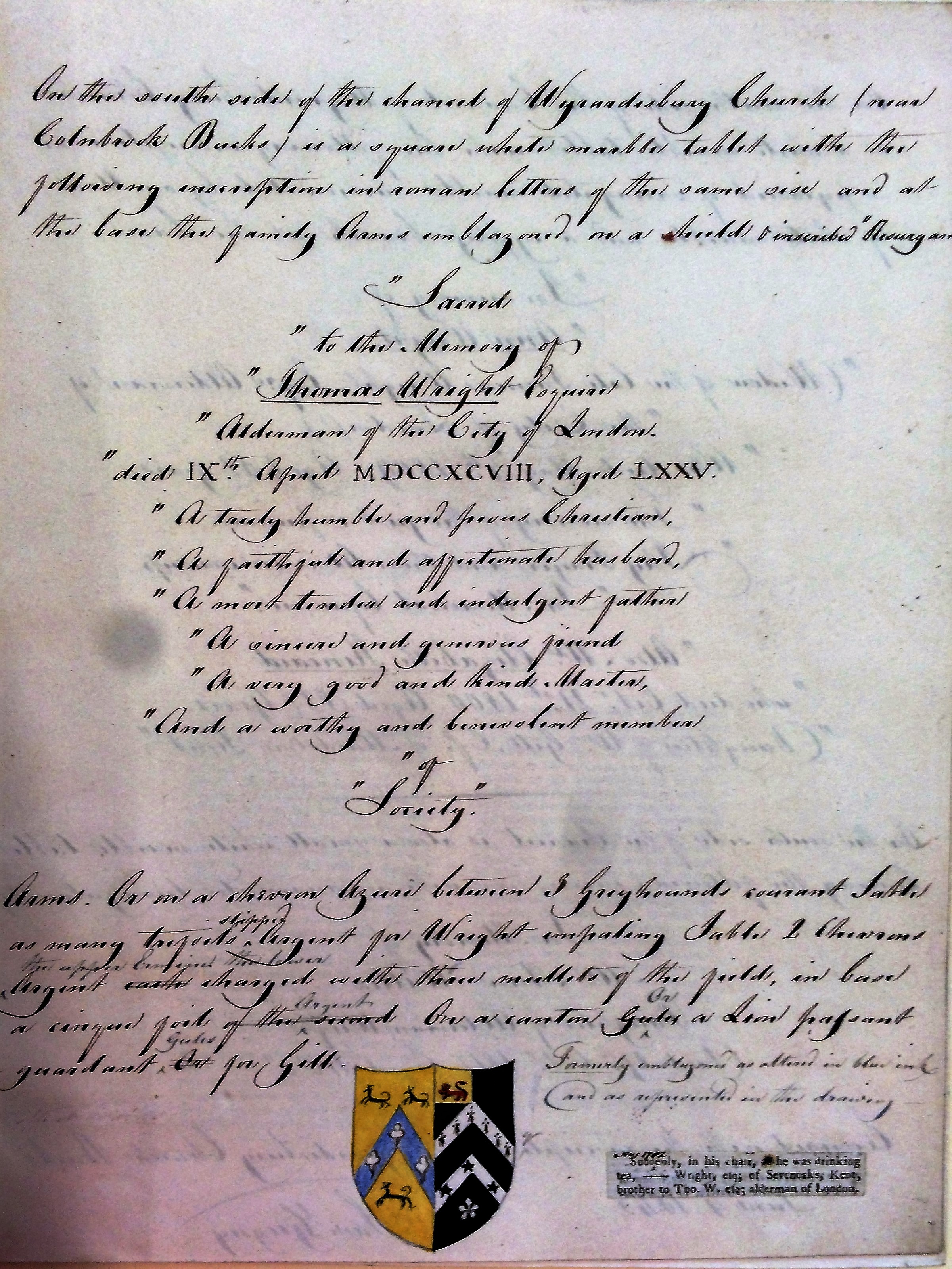

Wright family tomb inscription

Thomas Wright's memorial

Ann Wright's memorial