DULWICH COLLEGE BOARDING HOUSE

After WW2 Bell House welcomed some of Dulwich College's youngest boarders. For the next 45 years the house played host to hundreds of young pupils.

In 1948 Bell House opened its doors to around 30 junior College boarders, aged up to thirteen years. There was a house master who lived in with his wife and children, a matron and house tutor both of whom also lived in, and a ‘live-out’ tutor who came to the house to do supervising duties. In 1949 a bathroom was added to the first floor of the lodge and it became accommodation for College grounds staff. Bell House worked well as a boarding house. The original 1767 rooms on the second and third floors served as the housemaster’s family home with a living room, dining room and kitchen on the first floor and four bedrooms and a bathroom above them on the top floor. The housemaster’s study was on the ground floor off the hall, matron’s room was on the ground floor of the Victorian wing and she had use of the small kitchen next door and a bathroom opposite which she shared with the tutor, whose own room was on the first floor. The rest of the house was given over to the boys. The boys’ common room looked out over the garden and had a table for homework and space for table tennis. An adjoining room (now the chair store) held a billiard table. In 1970 it became a television room when a colour television arrived in time for the 1970 World Cup Final. At first the boys were not allowed to use the cellar but later there was a model railway train set and an old sofa down there. One dormitory (for the nine youngest boys and one older boy) was on the ground floor and known as the garden dorm, with another four dorms on the first floor: the captain’s (sleeping seven), the large front (aka ‘the middle’) and the small front (aka ‘the threesome’). The tutor’s dorm, which was opposite the tutor’s bedroom and slept four, was also known as the ‘naughty’ dorm, as the tutor could more easily keep an eye on any miscreants. The naughty dorm often lived up to its name. John Tudor remembers 1969, when there was a heavy snowfall. He was in the tutor’s dorm and made the mistake of letting a friend put his dressing gown on the balcony outside one of the windows. John climbed out to retrieve it whereupon the friend shut the window. Undaunted John simply shinned down the drainpipe and came back in through the garden door, creeping back to the dorm and none the worse for wear despite the cold weather.

In 1947 Bell House’s first housemaster was physics teacher Edward William Tapper (1905-1983), known as Bill to his colleagues but Ernie to the boys (for reasons unknown). The first matron was Lilian Day, who was soon replaced by Violet Law. Many boys were boarding at the College because their fathers were still serving in the armed forces in some capacity, following WW2. There were also College connections with Thailand and South America, so some pupils came from those countries. There were also pupils from around the country who were part of the Gilkes, or Dulwich, Experiment, a scheme to educate able children from poor backgrounds, where their school fees were met by local authorities. George Ray was one of these boys. He actually lived in Norwood but his father was a widower so George boarded for a year at Bell House in 1949, until his father’s remarriage meant he could become a day boy. He remembers Mr Penna, his house tutor, who would chat to the boys over tea and biscuits. In the late 1960s John Tudor remembers there were two house tutors: John Heath and JD Hewitt, the former of whom lived in a flat on Dulwich Common and who would hold recitals there for groups of boys where he would play some of the comic tunes around at the time. John remembers him being a gentle and kind man. Because he lived locally George Ray could return home for weekends and the school was flexible about this so long as he returned in time to report back to Bell House before school on Monday morning.

Bill Tapper had joined Dulwich College in 1930 and had introduced teaching radar to the boys and helped design the Science Block (recently replaced). He organised films (often Westerns) on Sunday evenings using his own projection equipment. in the School Science Block with the elder boys acting as projectionists. Tapper was a very tall man and boarder Geoffrey Taunton was a very small boy when he joined Bell House, so Tapper used to lift Geoffrey onto the table when he wanted to speak to him!

On Coronation Day 1953 the whole house wanted to watch the ceremony but there was not enough room to accommodate them all at the same time in front of the Tappers’ small television screen. Bill Tapper had the idea of giving half the boys the job of digging a hole for an ornamental pond on the south side of the house, they could then take turns watching a small TV and letting off steam digging in the garden. It might have been better to site the pond where a WW2 bomb had fallen in the centre of the garden: no matter how often the hole was filled in and the lawn levelled, the ground would always sink slightly in this area. Several boarders remember the Queen and Prince Philip passing through Dulwich later the same year and Michael Palmer has a photo of them as they flashed by in a blur.

Most of the garden was lawn, with a wilder part at the end (where Frank Dixon Close is now). There was a kitchen garden to the north side with an enormous greenhouse down the middle housing every kind of fruit imaginable. Gardening was the responsibility of the house master and Bill Tapper in particular was a keen gardener and kept the kitchen garden immaculate. Boarder George Ray remembers Tapper mowing the lawn with an early petrol mower, the first one George had seen. In the summer house tutor Terry Walsh often came back to his room after duty on Sundays to find a dish of strawberries or raspberries fresh from the garden and a small jug of cream. Tapper was unable to help however, the day Terry was marking books in his bedroom and a swarm of be es covered the window. A call to the head of biology proved an inspired idea as he turned out to be a bee expert and came equipped with protective overalls and a ladder. He moved the bees off the window, found the queen, popped her into a sack and when the rest of the swarm had followed her he transported them to a beekeeper friend in Kent.

David Smart taught geography at Dulwich College from 1966-1987 and for the first ten years he had an allotment in the kitchen garden at Bell House, running the length of the brick wall that divides the kitchen garden from the ornamental garden. He built a shed about halfway down where he kept his tools and he would transport his produce to his home in Roseway, Dulwich Village, in a wheelbarrow. In the 1960s and 70s the chief College groundsman, Jim Dixon, lived in Bell House Lodge and would grow prize chrysanthemums alongside David’s vegetables. Charles (Charlie) Parker was head groundsman at the College from 1978/9 to 1987 when he retired through ill health (he had Parkinson’s Disease). Mr and Mrs Parker lived at the Lodge and cleared much of the garden. He had a vegetable patch and also grew spectacular chrysanthemums. The Parkers’ daughter, Marion, remembers the medlar tree and her father talking about Roger Knight (her father played cricket and knew a thing or two about preparing wickets). She also recalls the frontage of the Lodge being used to film scenes for a period drama when a horse-drawn carriage entered through the large iron gates and drew up outside.

The kitchen garden then became an additional recreation area for the boys, though the grass had not the quality of the main lawn. Adrian Page remembers that one day in around 1971, some of the boarders located an abandoned motorbike in Dulwich Park and got it going round the kitchen garden. All went well until one boy got a bit carried away and collided with the garden wall at full throttle. Fortunately he was unhurt which was more than could be said for the motorbike!

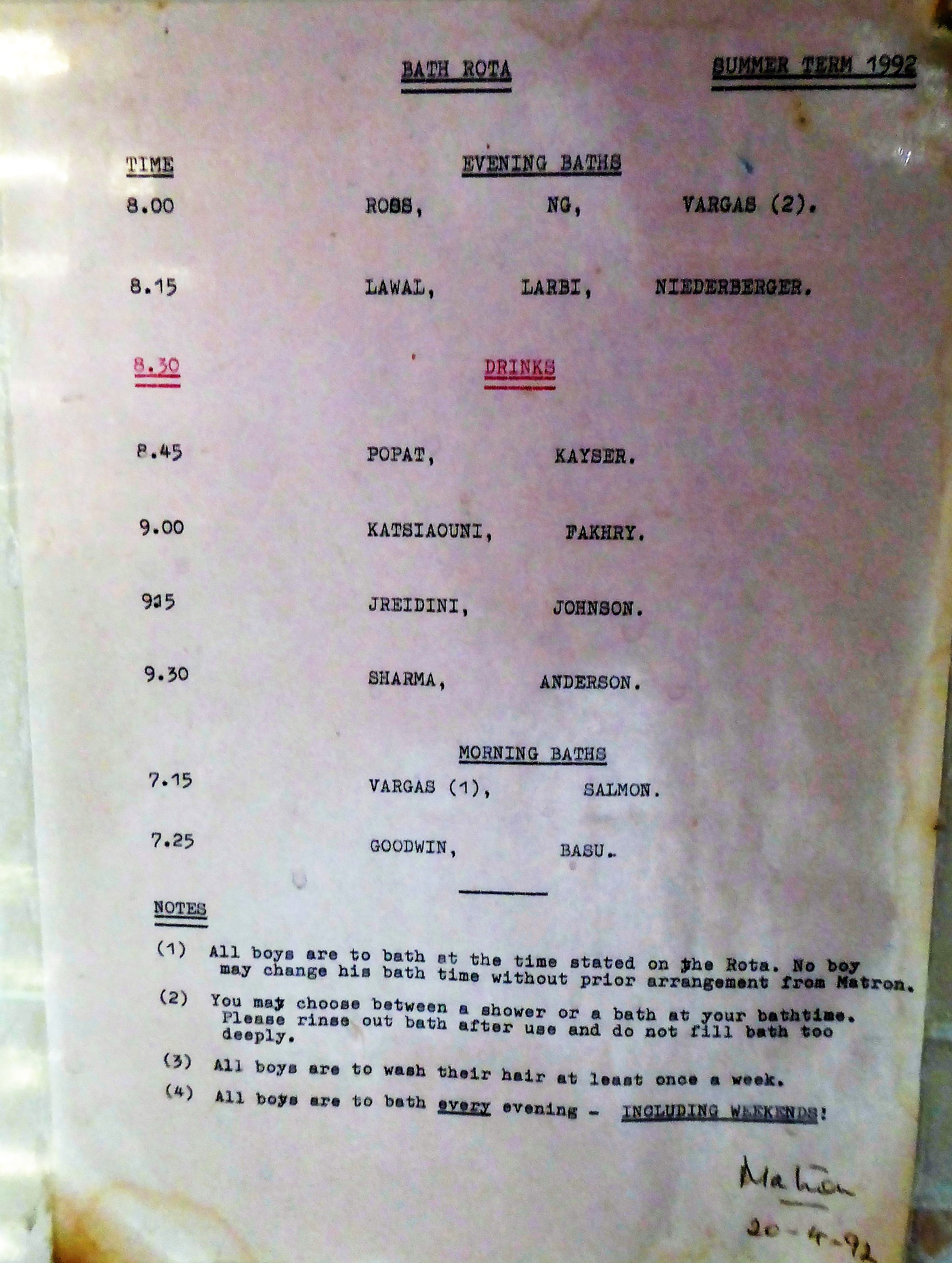

The Matron in the early 1950s was Miss Violet D Law who had joined Bell House in 1947 and the house tutor was Edward Penna. Matron had the job of keeping the boys looking reasonably neat and tidy while ‘Boots’ would come up from the College to clean the boys’ boots and shoes, though later the boys cleaned their own shoes which were carefully inspected. Michael Palmer, one of the very first boarders at Bell House, feels that there cannot be enough said in praise of the house matrons and says they were ‘quiet unassuming women, without whom the boarding houses would not have been able to function – dragon ladies most of them, but adored uniformly by the boys, and worth their weight in gold’. Others remember the matrons as being very cold and distant, not the mother figures that they might have wanted, given these were the College’s youngest boarders. John Tudor’s Matron was called Dotty Fivaz, a South African. Laundry was collected in huge wicker baskets in the ‘piano room’ on the ground floor corridor once a week (John distinctly remember the foul smell of sweaty socks in that room on laundry day). Socks had to be pinned together with a tiny golden-coloured safety pin and all items were labelled. Matron organised bath rotas and there was a line drawn in the bath to ensure boys did not waste water. In 1974, during the three-day week introduced to conserve electricity, boys shared baths and bathed by candlelight.

In the 1950s the boys woke at 7am when they took turns to wash in three baths, the last of which was always cold, by the 1960s the water was warm, by the 1970s the baths were replaced by showers. At 8am, they had breakfast in the buttery (from 1968 in the Christison Hall) at school then went back to Bell House before returning to school for registration at 9am, assembly at 9.10am and lessons starting at 9.25am (earlier on Saturdays). There was a 20 minute break mid-morning at 10.55am, and then lunch at 12.45pm, resuming classes at 2.15pm and finishing at 3.45pm (12.30pm on Saturdays). The boarders returned to Bell House after school before walking up again around 5pm for supper where at first the boys sat in house groups in order of seniority with the house captain sitting next to the House Master and the youngest boy next to Matron. Later, the seating was on three parallel tables with the House Master, Matron or the House Tutor at one end and ten boys per table. Boys rotated one place clockwise each day so they sat next to the adult every so often but more importantly opposite different fellow boarders each day. The boys took turns in pairs to serve the dishes on their side of the table, and to clear away the empty plates – and the plates always were empty – very few leftovers despite the institutional nature of the meals. When the boarding house first opened meals would have been limited by food rationing. There was a cupboard in the dining room for personal jam jars. When Tilak Conrad arrived from Sri Lanka and joined Bell House in 1968 he was permitted to bring his ‘special sauce’ from home. It was a red sauce which looked to his fellow boarders like tomato ketchup, a coveted and banned relish. Tilak generously shared his sauce with his new friends, not realising they were unused to spicy food. Bell House boarders having smothered their food in chili sauce thinking it was ketchup, were then made to sit until they had cleared their plates. After meals were over, the Master could often be seen on his old upright bicycle riding back to his home across the road, with a bucket of scraps on the handlebars for feeding his chickens. John Tudor remembers that his house master, David Knight, was a diabetic and took salt with his cornflakes. John recalls that Knight would rotate seating plans so that infrequently but regularly each boarder got to sit near to Knight and were this under the microscope - Knight was not reluctant to provide instruction in good table manners!

Adrian Page remembers that the routine had changed a little by the late 60s. Boarders were woken at 6:45am, they would then wash, get dressed and gather school books and any PE kit if and walk to breakfast served at 8am. Then walk up College Road on the West side only as 30 boys together on the Bell House side between the white posts and chains would have blocked the path for anyone else. Boarders had to cross College Road immediately opposite the house and had to go round the Village side of the lamp post opposite – there was no crossing on the diagonal to save time! After breakfast boys would go to the Lower School Playground as by then there was no going back to Bell House after breakfast. In the evening dinner was at 6pm so boarders would leave Bell about 6.35pm. They would return to start homework (prep) at about 6:45pm. Each year group had a fixed amount of time, around 30 minutes for the youngest with 90 minutes for the eldest. Prep was supervised by the Duty Master and if boys finished before their set time they could show their work to him, and hopefully then leave and go to the dormitory or down to the cellar. The Duty Masters did not offer a homework help service!

At around 8pm to 8:30pm each evening there were evening prayers followed by a House meeting where any announcements would be made, pocket money given out etc. Evening prayers consisted of a short New Testament reading, a prayer and the ‘Our Father’. Non-Christian boys sat this out. The reading was done by each boy in turn to a strict rota on the notice board. The reader could choose which 10 or so verses to read and it was often a bit of a game to choose something recognisable like a parable or a selection from say ‘Letters to the Corinthians’ which was probably incomprehensible even to the Corinthians! In the evening there were prayers and the boys took turns to read a lesson which they would choose themselves, though it had to be approved by a master. Boarder Richard Mattick remembers that sometimes boys would choose a passage that included a long genealogical list of names (x begat y etc) which amused the listeners very much.

Evenings finished with a bath bun and a quarter pint of milk, with hot cocoa on Sundays, dispensed from Matron’s kitchen on the front side of the House near the back door. At the weekend there were lessons on Saturday morning, sport in the afternoon and more prep at night. Prep, supervised by a tutor, took place in the Common Room and Billiard Room - the Billiard Room being out of line-of-sight of the tutor and thus a plum place to sit. Sunday’s routine was chapel in the morning with the afternoon being the only significant free time the boys had during the week, though in the 50s and 60s there was compulsory house rugby before free time. And then the treat of Mr Tapper’s film show on Sunday evening. One boarder remembers, ‘What today seems extraordinary is that our shoes were cleaned every night by Mr Roly, inevitably nicknamed Boots’. In the 60s Mr Roly was replaced by Mr Ellis who cleaned the shoes on a bench by the window near the shoe pigeonholes. Roly would number the shoes on the sole with the corresponding number of the pigeonhole so that the boys always knew which shoes were theirs. From 1968 the boys had to clean their own shoes. The shoe pigeonholes are still in place at Bell House as is the walk-in cupboard where Matron dispensed the twice-weekly quotas of starched and ironed shirts with detachable collars so stiff they sometime drew blood when they cut into the neck. John Tudor remembers that boys learned very quickly to keep their head still as otherwise they ended up with raw necks, though by the second term pupils maliciously welcomed the idea of new boys having to go through it as they had. Master Charles Lloyd abandoned detachable collars as part of his modernising campaign in about 1968 (he also introduced weekly boarding in 1970/71.) Michael Palmer, one of the very first boarders at Bell House, feels that there cannot be enough said in praise of the house matrons and says they were ‘quiet unassuming women, without whom the boarding houses would not have been able to function – dragon ladies most of them, but adored uniformly by the boys, and worth their weight in gold’.

Leonard Cornish was a pupil at Dulwich College from 1955 to 1962. His father had been posted to the British Embassy in Baghdad and as there was no English secondary school in Baghdad at that time his parents needed to find a boarding school. Dulwich invited him for interview which required flying back to London alone aged 11. An embassy staff member who was travelling on the same flight kept an eye on him. He was interviewed by Ronald Groves. Leonard remembers Groves being very friendly and asking him to read a few pages of a book. On his first day at Dulwich, Leonard’s uncle, who was also his guardian, took him to Bell House and Leonard vividly recalls the Bell House drive. While his uncle went to chat to Mr Tapper, a boy took Leonard to play snooker. By the time his uncle returned he felt well settled and at ease. He says that Bell House had a very happy atmosphere.

One of the boarders had lost an eye as a baby and had a glass replacement which led inevitably to him being given the nickname Popeye. When the boy joined Bell House, Terry Walsh was instructed in how to put the eye in and take it out again. On the boy’s first morning there came a knock at the house tutor’s door and Terry assumed he needed help with his eye. No sir, the boy said, I can’t tie my tie. As the boy grew the glass eye didn’t and so became loose. It was used in pranks like being dropped at inopportune moments or being rolled across desks to distract teachers. When Matron made her dormitory round late at night the boy would take the glass eye out and, shining a torch through it, slowly move it round above his bed. Leonard Cornish has a more fragrant memory of bedtime at Bell House when house tutor, Terry Walsh, brought his fiancée to say goodnight to the boys. A strong smell of perfume wafted through the dorm and persisted, making this a particularly memorable occasion.

After ten years at Bell House Tapper applied to the College for permission to build a retirement cottage in the walled garden. The College were amenable to this proposal but the Governors refused permission. On his retirement from the College he became Secretary of the Science Masters Association and was later awarded the OBE. His wife, Barry, gave her time to the Distressed Gentlefolks Association.

In 1957 Tapper was succeeded by David Verdon Knight who had been a pupil at the College and school captain. In 1942, after Cambridge, he returned to teach at Dulwich, his plan to join the army having been scuppered when it was discovered he was diabetic, a condition not so easily treatable in those days. He was asked to join the school ‘for a term or so’ and stayed for thirty-eight years. He had always longed to have the post of housemaster and was delighted to take over what he called one of the most gracious buildings in Dulwich. He said that the twelve years he spent as housemaster of Bell House were some of the most enjoyable years of his life and his wife, Patricia, also remembers her time as ‘housemistress’ of Bell House as a time of ‘happiness and fulfilment’.

In the holidays David and Patricia Knight would hold celebrated New Year’s Eve parties in the ‘Garden Dorm’ (what had been the drawing room in earlier times) for around seventy people. Members of staff were offered accommodation for the night in the upstairs dorms. Once Patricia and the house tutor, Geoff Waterworth, climbed up onto the roof to ring ‘a few mellow notes’ on the bell which gives the house its name. Knight once had a visitor who told of her childhood at Bell House in the 1870s. This must have been either Alice or Annie Gowan and she told of climbing over the roof of the coach house (always known as the groundsman’s cottage) and also of peeping over the banisters to watch footmen usher in the guests at her parents’ parties. She particularly remembered a small copper beech tree she used to climb, which she pointed out to Knight was now over seventy feet high. This same tree was often climbed by the boarders of Bell House too, and on occasions by Patricia Knight herself when she wanted to avoid particular people.

During the flu epidemic of 1957 one of the dormitories in Bell House had to be turned into a sick bay, as the school sanatorium was full. The doctor would solemnly progress through the dorm, followed by Miss Law the Matron and Patricia Knight. Following in their wake came Domino, the Knight family’s blue-roan spaniel, ‘gathering up as many slippers in his mouth as he could’. Domino was expelled when he nearly tripped the doctor up. Boarders ate all meals, even breakfast, up at school rather than at Bell House although food for the invalids was brought down from the school but usually given to Domino as it consisted of ‘gristly slices of cold meat and even colder potatoes’. Patricia would supplement rations for the sick boys from her own purse.

On Bonfire Night one year the houses of Frank Dixon Close (which run along the back boundary of Bell House) hosted a joint fireworks display. The sick boys were allowed to watch from the windows and everyone else leant over the garden fence as an enormous cardboard box filled with fireworks was ceremoniously carried to the grass circle in the middle of the Close. The first firework was lit to the usual oohs and aahs and as it died away one of its sparks fell into the cardboard box and set off all the fireworks at once, causing ‘a Vesuvius-like explosion’. Knight describes it magnificently:

…fiery streaks, whistles, flashes and bangs. Rockets shrieked waist-high above the ground, ricocheting off walls and trees; squibs bounded about the place; golden rain showered imperiously upwards while Catherine Wheels swivelled frantically on the ground; Jacks in the Box shot stars into the dark and parachutes hung in the branches above. Children screamed whilst parents picked up their offspring and ran. From the Bell House garden it was a tremendous spectacle, though brief. That no one was hurt was a miracle.

The only casualty was a boarder who had been absent-mindedly chewing one of his coat’s buttons when the violence of the explosion caused him to swallow it. He was slapped on the back, turned upside down then taken to hospital from where he returned with instructions to wait for the button to pass of its own accord. The button appeared within a few days, to the relief of Matron and of Knight who had not relished telephoning the boy’s parents in Venezuela to explain the incident. In the meantime one of the Frank Dixon Close residents had dashed down to Mr Green’s toy shop in the Village, bought up all the fireworks and taken them back for a show which most of the spectators watched from the safety of their houses. In other years Bell House hosted Bonfire Night parties when the scouts came to join the boys in building a bonfire and cooking sausages.

David Knight was a very traditional schoolmaster but notwithstanding that, the Knights had warm relationships with their charges. Patricia would help them with their ties and their stiff detachable collars. When a boy’s birthday fell in term-time, she would personally give him a small gift. As each boy moved on from Bell House Knight would have individual chats with each of them. For example, he asked Leonard Cornish if he had thought of going to university. Leonard replied that he hadn’t to which Knight replied ‘Well, you should’, sowing a seed which germinated when Leonard was in the 5th form and which led to a university education. Knight was remembered by boys long after they had left the College. One boy, who went on to fight in the Falklands Conflict, took time to send Knight a photograph of Ernest Shackleton’s grave on South Georgia, knowing that Shackleton (also a Dulwich pupil) and his epic journey were passions of Knight’s. Not all the boys were so fondly remembered, one boy leaned out of his dormitory window and sprayed weedkiller over Matron’s window-box below. After that she blamed him for every misdemeanour she came across. She was even less forgiving the time he hid a mouse in her handbag. One boy discovered a chimney-like shaft accessible from an outside wall of the house. He climbed into it, finding that it went up to the first floor then crossed the space between the ground floor ceiling and the floor of the rooms above. He got stuck and needed some smaller boys sent after him to pull him out. He emerged protesting that he was just about to explore further, despite the rat he encountered, but Knight forbade him from trying again. His father, a thriller writer who also wrote screenplays for some of the James Bond films, agreed with Knight that he was ‘an absolute rascal’. Described as a ‘Just William’ character, this boy returned as an adult to visit Bell House in the late 1960s, every inch the responsible adult and immaculate in suit, bowler hat and tightly furled umbrella.

That the Knights succeeded in creating a home-from-home for the pupils is illustrated by the eleven-year-old who, in the Sanatorium for a minor illness, decided he preferred to be at home in Bell House so left at 12.45 am, in just his pyjamas with nothing on his feet. Tony Powell remembers how much they enjoyed Patricia Knight’s sense of humour. She often made them ‘apple-pie’ beds and once, on the last night of term before the Christmas holidays, she sewed up the feet of all their pyjama trousers!

Knight children, Roger and Cheryl, grew up at Bell House and remember the happy times they all had there, including sliding down the banisters and even climbing out of their bedroom windows to explore the roof, much to the consternation of their mother. Their father built a rock garden culminating in a waterfall into the pond outside the study.

Roger was responsible for mowing the lawn which took two and a half hours as most of the garden was grass. He was also responsible for stoking the boiler and keeping it alight, he remembers it was always a temperamental machine. The Knight children remember their mother ringing a handbell from the first floor to call them in from the garden for meals; they still have the bell. Roger and Cheryl went to Dulwich schools and both remember happy birthday parties at the house. Roger went on to teach at Dulwich College, was captain of Surrey cricket and president of the MCC. Leonard Cornish, who boarded at Bell House, recalls many hours spent in the garden playing mini cricket with Roger and other pupils. Later, Roger and his wife stayed with the Cornishes in Hong Kong when he took Surrey Cricket Club on a tour and Leonard remembers watching them play at the Hong Kong Cricket Club at Wong Nei Chong Gap.

There were lots of extra-curricular activities at Bell House. Knight liked the boys to be fit for the highlight of the annual rugby matches against the other boarding houses so would take them on pre-breakfast runs in Dulwich Park though after the first one or two he realised the boys were much fitter than him so took his bicycle after that. At Dulwich the boarding house that came top of all sporting activities, house music and various other competitions was named ‘Cock House’ and Knight was always delighted when Bell House won this title. John Tudor was proud to be house captain in 1970 when Bell House won Cock House. He remembers playing rugby in the cock house competition during a very cold spell. His mother came to watch, attired in fur and bearing a massive WW2 RAF Thermos flask of Bovril that she gave the team to warm us up. Very welcome it was and the Bell House boys were congratulating themselves on their good fortune and advantage over the opposite team when John’s mother decided it would be only fair to dispense said Bovril to the other house. John says this grievance is still brought up by some of his fellow team members when they meet up.

Regular activities included trips to Windsor Castle, the Old Vic and Streatham ice rink. Tony Powell’s uncle was a translator in Russia so sent his nephew real Russian skating boots. Knight encouraged the boys to put on sketches and shows and helped with rehearsals. He arranged for masters like John Heath, who taught Classics and Music, and Alan Morgan, head of music, to perform for the boys; the musicians on the first-floor landing where there was a piano while down in the hall below sat the guests on chairs and the boys on the floor. Christmas carols were always sung around the Christmas tree in the hall with one of the boys precariously carrying a candle lantern on the end of a pole. Mrs Knight would then give each boy a small present.

Knight also made his own films for the boys’ amusement, recording ordinary life at Bell House: boys doing their homework or walking down to the chapel on Sundays, interspersed with tricks like a dorm’s beds being made in a flash, or tiger skin rugs coming to life. John Tudor remembers them to be very creative and funny and he appeared in one where he was raking leaves but Knight reversed the film so that eventually John was covered in leaves with just his head poking out. John said that ‘Thinking about it now the amount of thought and effort applied to entertain us by DVK and the house tutors was really extraordinary’.

Outings were arranged, by train to Brighton or by boat to Hampton Court. Roger had an elaborate model railway train set which ran around his bedroom, later it was transferred to the cellar and used to film elaborate crashes using Knight’s cine camera. Patricia also used it to distract homesick boys. Boys had an account at the grocery in Dulwich Village ostensibly for buying fresh fruit. However, when the grocer installed a freezer and started selling frozen cakes, the termly bills increased exponentially until parental anger put a stop to it.

At the end of his tenure at Bell House, Knight was presented with a silver salver inscribed with the word Bell. The Knights moved to Hollybrow, at the top of Sydenham Hill and described by Knight as a ‘mini-Bell’.

At this time there was no footpath or pavement in front of Bell House, the property extended to the road. After Frank Dixon Way had been built, an issue emerged of children walking to school and having to walk in the road. Consequently a strip of land 3ft 6in was taken from Bell House to make the footpath we see in front of Bell House today.

Terry Walsh joined Bell House as house tutor in the summer of 1955. His salary was £700 pa including a £75 pa supplement for having done two years National Service and for holding a diploma in education. With bed and board paid a young house tutor had next to no outgoings so his salary was all disposable income. The tutor’s room overlooked the carriage drive at the front of Bell House and he shared use of a ground floor bathroom with Matron. The ‘private side’, the part of the house reserved for the housemaster and his family, was separated from the boarding side by a door and bell and was generally out of bounds, unless invited in by the family. The house tutor, Matron, Joe the handyman and the boys would use the back stairs and the side door on a day-to-day basis: the front door and main stairs were reserved for the family and parents. David Knight kept a ‘nightstick, similar to a policeman’s truncheon, beside the front door, not for the boys of course, but for any potential burglars. In the morning David Knight did not like the boys waking to the bell; he preferred to go round each dorm and wake them up himself. The boys dressed then assembled for the walk up to school for breakfast; boys were always escorted to and from school at this time. The corridor between the back stairs and the back door was filled with indoor and outdoor shoes, coats, caps, bags. Slippers were also stored here, to be changed into whenever the boys came back to the house.

Terry remembers the London smogs when cold weather combined with pollution from coal fires to form a thick mixture of smoke and fog. It turned day into night and was thick enough to cause him to lose his way between school buildings. Leonard Cornish remembers them too, and says the boys would walking up to school holding hands so that they didn't get lost At that time the masters wore stiff white collars which got so filthy that they were given permission to use paper disposable collars instead. These were replaced at lunchtime by which time they were already black with soot.

At this time there was school on Saturday morning followed by compulsory games in the afternoon. Boys not playing in a match for the school or their house were expected to support the first team and there was a register taken before and after games to ensure nobody sloped off early. On Sundays the boys had breakfast an hour later following which they went back to Bell House to get ready for chapel at 11am in pin stripe trousers and charcoal herringbone jackets. After breakfast those in the Chapel Choir had to wait for the Music Master Alan Morgan to arrive at school. Usually there was about half an hour to wait and since the cloisters had been enclosed recently, they would play football with a tennis ball in the cloisters. They then had choir practice before heading back to Bell House to get their appearance checked by Matron – woe betide you if you didn’t pass muster. They would line up in the corridor leading to the back door and file past the house tutor who would hand out a prayer book, a clean hankie (if needed) and a penny for the collection. Some boys had to be reminded that sterling was the only acceptable currency for the chapel collection, lest they were tempted to keep the penny and offload a coin from another country. The boys always looked forward to an annual sermon from a monk who was very entertaining. Michael Palmer remembers that Anglican observance and ritual ran through the boys’ lives from one end of the day to the other, starting with Grace before meals, to morning assembly in the Great Hall, to evening reading and prayers at bedtime, and of course compulsory attendance at Chapel on Sunday mornings. Boarders at Bell House had the special privilege of ringing the chapel bell for Sunday services. Leonard Cornish remembers one Sunday, after a heavy snowfall, chapel was cancelled and the boys spent the morning playing in the snow outside Bell House.

When Michael Palmer was a boarder the bathroom had three baths arranged in a T-formation. There were two bath shifts every evening, loosely supervised by the house tutor to make sure that boys washed behind their ears, and that the first shift did not hog all the hot water. They had one bath a week (there were around 30 boys to get through) but there were also baths after games on Wednesdays and Saturdays. By contrast, Blew and Ivyholme boarding houses each had a large communal bath which could take a dozen boys or more which was much more practical after games.

Christopher Elston was a boarder at Bell House from 1962-65. It was his first time away from his parents who lived in Germany and after an initial spell of homesickness he settled happily into life at Bell House. His bed was in a corner of the garden dorm and he had a share of the chest of drawers beside it with his tuck box underneath his bed. After a year he moved into an upstairs dorm. Days were full of schoolwork, sport, prep and other activities but there was time for table tennis in the common room. billiards in the room next door and Sunday evening film shows. He fondly remembers David Knight’s treasure hunts around the house and garden: the housemaster’s blue Austin, always parked outside on the drive, furnished a bovine clue connected with its registration number MOO99. Christopher vividly remembers being in the common room doing his prep on 22 November 1963 when a master came in and told the boys that John F Kennedy, the American president, had been assassinated. The radio on the common room mantelpiece was then turned on for the news. Russ Kane and Anthony Frankford remember boarding at Bell House when Kennedy died and also when Churchill died and hearing the radio news on both occasions. Michael Palmer recalls that later the radio was normally tuned to the Home Service or the Light Programme or sometimes to Radio Luxembourg – the boys would decide amongst themselves. Russ Kane and Anthony Frankford remember Sunday evenings listening to ‘Pick of the Pops’ with Alan Freeman on the Light Programme.

In January 1963 a new Matron was appointed: Mrs Mary Parkinson, who replaced Miss IA Greensill and Mrs Tebbit who had been appointed following the retirement of Miss Laws in 1962. Turnover of matrons was high at this time as Mrs Parkinson was replaced by Miss KM Peace in November the same year, at a salary of £375 pa. Miss Lesley Angus and Miss KM Grey were also appointed matron around this time. Rules were strictly adhered to in the 60s, one deterrent being the cane which was kept in Mr Knight’s study, another punishment being an hour’s work in the garden or writing lines or ‘Pages’. Adrian Page remembers that when Knight was housemaster there was a tiger skin rug outside Knight’s study, complete with head, glass eyes and a full set of teeth! Christopher Elston, who came back to visit the house, told us he was proud to be made a monitor in his third year and was one of the last boys to fag for another as the tradition ended during his time at the College. When Christopher was a boarder life at Bell House was very formal and he says only surnames were used never first names. Adrian Page confirms this and recalls Knight gathering the boarders together and making it very clear that ONLY surnames were to be heard. Adrian thought it might just be permissible to use a first name in a one-to-one conversation when walking up College Road to school but it was clear that at no other time were first names acceptable. Letters home were written on a weekly basis, to be left unsealed on the hall table, for the housemaster to post (and read if he was so minded). Matron was formal and distant, not the motherly figure of later holders if the post. Older boys set a test on Dulwich College general knowledge for new boys after their first term, with questions about rules, houses, hierarchy, and the architecture and arrangement of the school: what are the ‘buds of knowledge’ (the flower shaped panels in the otherwise red-brick structure of the main school building) who is the school founder (Edward Alleyn), etc. There was a penalty of drinking salted orange juice if you failed.

In 1969 John ‘Spud’ McInley, who had been a pupil at Dulwich College and returned to teach French, became housemaster. He had joined the College as a boy in 1939 as part of the ‘Dulwich Experiment’ when Booth was Master and was living in Bell House. John moved in with his wife Alice, son Phil, daughter Jacqueline and Duke the dog. John’s father who had himself been a schoolmaster, also lived with them and had his own room on the top floor of the Georgian part of the house. He particularly enjoyed attending chapel with the boys on Sundays. Alice worked with Russell Vernon, the Estate architect, and made some changes to the house including the removal of the asbestos partition on the top floor which divided the housemaster’s bedrooms from the rest of the house. It was Alice who chose the yellow stairs and landing carpet which was still in use until 2018. She would host dinner parties on the landing to take full advantage of the beautiful Venetian window on the first floor.

John McInley ran things in a more relaxed way than the other boarding houses. His matrons: M Brown, J Grimwood, H Hobkirk, M Simmonds and Janice Camp, were an integral part of his team and he took a great deal of care over their appointment, knowing that they, more than anyone else, were acting in loco parentis. He introduced more homely touches like replacing the two huge baths with smaller, individual baths, and later with showers. When he left Bell House there was a huge turnout for his leaving party which was organised by Fergus Jamieson, his house tutor who also deputised for McInley as house master on occasions.

The ‘live-in’ house tutors were generally young and often at the start of their careers. Fergus Jamieson began his career teaching at Dulwich College and was the tutor at Bell House from 1970-75 together with R Hore. Jamieson remembers his room fondly with its bright sunny aspect looking out over the trees and shrubs covering the ha-ha. There was plenty of room with a bed, table, two armchairs by the windows and two built in cupboards and Fergus decorated with large posters of famous composers. Adrian Page remembers the care with which Jamieson would undertake his pastoral duties, and the regular chats he would have with boys over tea and toast. John Tudor remembers that in 1967/8 his house tutor Mr. Hewitt was replaced by Randall Stephens, and Matron Fivaz by Lesley Angus. ‘Rocky’ Randall was a good sportsman and drove an open-top sports car, often accompanied by Miss Angus. They were both instrumental in modernising thinking in and brought a satirical wit to the house.

In return for their free accommodation young tutors were given something of a crash course in dealing with energetic young schoolboys and the boys sometimes tested the rules to the limit. A chair just outside the housemaster’s study awaited miscreants, and punishments (known as fatigues) such as weeding the drive were handed out for minor misdemeanours. More serious offences were dealt with by corporal punishment or a transfer into the ‘naughty’ dorm where the tutor could keep a closer eye. John Tudor recalls another minor punishment called ‘Pages’, where pupils had to write neatly with each letter hitting the top and bottom of a line exactly. While this was tedious, it could also be made harder by being assigned a specific topic which necessitated a lot of research.

The house captain and around five house monitors were also tasked with keeping order among the 30 or so boarders. The House Captain could give a ‘House Captain’s Report’ which required the victim to attend (report to) the House Captain before the wake-up bell in the morning, The House Captain would then give the transgressor ‘3 minutes to get into rugby kit with boots’ – 2.59 later the child appears clad in rugby attire. Or ‘1 minute to get into swimming trunks’ or ‘4 minutes into Sunday best’ etc. But it was not all strictness and punishments: boarders during McInley’s time have spoken of feeling bold enough to listen to Radio Luxemburg under the covers after lights out, safe in the knowledge that the punishment would not be too severe should they be discovered.

Dorms held anything from four to twelve beds. Each boy had a small amount of space to call his own: a chair to hang his clothes, half of a small chest of drawers, and a tuck box kept under his bed. John Tudor remembers that in the late 1960s, the mattresses were straw. He remembers the arrival of pink sponge mattresses in about 1968, a very welcome change. They were delivered individually wrapped in cellophane and piled outside the front of the house under the front dorm windows which for the boarders was too good an opportunity to miss. Immediately there was a queue of boys jumping out of the first-floor dorm windows onto the mattresses below. Sheets and blankets were provided by the school and each boy brought his own blanket to cover the bed in a plaid or tartan pattern. Sports kit and shoes were stored downstairs in the long corridor leading to the side door, trunks in the cellar while sponge bags hung on hooks in the bathroom. Tuesday was laundry day and Matron had a large laundry room on the ground floor. Rugby kit was not washed after use but, wet and mud caked, was hung over horizontal metal hot water pipes in the cellar. By the time it was next needed it would be as rigid as cardboard but hitting it would cause some of the caked mud to fall off and as soon as it got wet again it would feel as good as new! With sport twice a week there would be not time for kit to go to the external laundry and come back again. There were two cleaning ladies to keep the house in order. Friday was pocket money day and boys would line up outside the housemaster’s study to collect their cash. Russ Kane remembers that no boy was allowed to have more than 5 shillings in total at any one time. If parents sent extra pocket money then the house tutor would hold it. Fergus Jamieson remembers being the ‘bank’ for any extra money parents might have left for their sons. If the boys ever needed money above their normal allowance, for a particular trip or event, they would ask Mr Jamieson.

During the school day boarders were allowed to return to Bell House from school with special permission if they had forgotten something vital but usually they journeyed from Bell House to school in a crocodile in pairs. They were taken across College Road immediately after leaving Bell House and walked up College Road to the lights at the junction with Dulwich Common. After crossing they walked down to the Library Gate (where the vehicle entrance is now). John Tudor clearly remembers his tutor John Heath’s stentorian tones: ‘Cross now Bell House!’. The 1970s were a less monitored time and boarders had a large amount of freedom. They would walk between the College and Bell House unsupervised. Richard Mattick remembers the walk up College Road to the Christison Hall for the evening meal gave the opportunity for pupils to play tricks on each other on the way. One evening he removed a younger boy’s cap and put it on the roof of what he thought was a parked van, only to watch the van drive away with the cap. His parents had to give the fellow pupil the cost of the cap, but as caps were no longer compulsory, the ‘victim” took great pleasure in buying a scarf with the money.

Boys could move around London or even travel home alone at the end of term. The freedom even extended to boys buying their own tickets home from the travel agent in Dulwich Village. Boarders were allowed home for half term, and also for two ‘visiting’ or exeat weekends - one in each half of term, though there was still Saturday morning school which meant you couldn’t leave until lunchtime on Saturdays and had to be back at Bell House by 6pm on Sunday. John Tudor’s mother lived locally on Half Moon Lane so often his friends who lived abroad would spend their visiting weekends at his home. They would then reciprocate at half terms meaning John got to spend time abroad such as breaks in Brussels with his friend Miles, later Professor, Hewstone.

There was a wide variety of entertainment available. House playtime was between school and supper time. In the summer boarders would play in the garden, after seeking permission from the master on duty, often football or rounders but to really let off steam they played ‘British bulldog’, a fairly hazardous game with flexible rules involving large numbers of boys and a lot of running around and tackling each other. They also played ‘Kick The Can’ an outdoor game which combines tag, hide and seek and capture the flag. The woods next to the lawn made great places to hide and the big trees that were simply made to climb. More civilised games of cards (mostly bridge), table tennis and billiards were played in the house and often in the cellar, where the senior boys also had a ‘band room’ with electric guitars and drums. There was also a record player in the 70s. Once a year, each dormitory had to perform a play for the rest of the house in the Common Room, the scripts being provided by the house tutors based on the number of boys in the dorm. Sometimes two dorms were merged. John Tudor remembers performing in a play called ‘In a dentist’s waiting room’ by AJ Talbot with a cast of seven (three from the threesome and four from the tutor’s dorm). The TV room had wooden chairs lined up in rows, nothing as comfortable as a sofa, though oddly, down in the cellar there was a small room furnished with a sofa for the older boys to use. In the late 60s one room in the cellar was called the ‘Sal’ and was used to host a version of the wall game which was very physical and quite brutal, and certainly not rule-based. There was also a photographic darkroom in the cellar. The old water pump is still in the cellar today and Adrian Page recalls there was a rumour it would flood the housemaster’s kitchen. He says of course the boys tried it – it didn’t.

Given the nature of the times, sadly there would almost certainly have been some bullying going on, but none of the boarders that we have spoken to has said they were bullied, though some knew of boys who were. Some boarders who lived in London, or who had come from Dulwich College Prep, now Dulwich Prep London, had friends amongst the day boys but boarders spent so much time as a group that they became what John Tudor describes as ‘a sort of family, with all the stresses and tensions that families have. It was like having 28 brothers to look after you; we might scrap amongst ourselves but God help anyone picking on one of us’. Boarders grew close because they had to be resilient; they could not go home and tell their troubles to their parents. John Tudor tells of protecting boys with genuine problems such as one with severe asthma; his fellow boarders made sure he never had to do anything that might endanger him and he was never teased about his ailment.

Design & Technology teacher Tony Salter took over as housemaster in 1977, moving in with his wife Judith and daughters Emma and Joanna and dogs Minstrel and Dougie. His tutors included FJ Loveder, BG Thompson, JR Jennings, DA Crehan and B Cumberland. Salter was heavily involved in the school cadet corps and would organise camping trips in the Brecon Beacons. He was also a member of the Territorial Army and helped organise the Lord Mayor’s Show. He was described as a ‘fine soldier whose service to Queen and country will not be forgotten’. In his spare time he was interested in clocks and would spend hours taking them apart and putting them back together in perfect working order. Judith remembers there was lots to do: the boys would play with the Salter family’s two Great Danes, Tasha and Lara; there was a snooker table in the hall and the boys would be taken on trips to Brighton at the weekend. On 5 November they would all go to see the fireworks at Crystal Palace. Judith would try to make the house a home-away-from-home for the boarders and when it was their birthday she would bake them a birthday cake with their initials iced on top.

The last housemaster of Bell House was Ian Senior who moved here with his wife, Astrid and two sons in 1987. Matron, the house tutor and around thirty 7-13 year olds completed the household. There was a fair amount of marshalling of boys, as the South Circular stood between the boarding house and the school. Each morning the boys would be woken by the prefect with a handbell. When they were ready two members of staff would take the boys up to school for their breakfast. The boys had to take with them everything they needed for their school day as now they were not allowed back to the boarding house before the end of the school day. At the end of the day they could come back on their own but at 6pm they were gathered together again to walk up to school for their supper before being shepherded back to Bell House again to do their homework and get their bags ready for the next day. Some boys were more responsible than others and so could be given a little bit more leeway: one boy, who learnt to fly before he could drive, would hire a plane at Biggin Hill and fly himself home to Luxembourg at the end of term.

Weekly boarders would go home for the weekend but termly boarders needed to be entertained and Ian remembers plenty of culturally enriching trips to galleries and museums which, together with sports practice, matches and Saturday morning school lessons, kept most boys out of trouble. At Christmas the great and the good of Dulwich were invited to join the boarders for their last meal of term. These meals were a particularly stressful time for Ian and his staff. They were exhausted from the term just finished, the boys were exuberant at the thought of the holidays to come and the masters had a hard time keeping the boys well-behaved in front of the Dulwich dignitaries. Similarly, on Founder’s Day parents and guardians were often invited for strawberries and tea by the house master in the garden of Bell House. These too were often tense affairs because, as John Tudor puts it, ‘our interpretation of events and the house master’s were often not well aligned’.

On the last day or term, after chapel, boys were collected by their parents or guardians until eventually, towards the end of the afternoon, Ian Senior would notice a hush had descended on Bell House. He would make a tour of the rooms to find the house was now empty save for him and his family. For the next few weeks, with the large house and huge gardens to themselves, Ian felt like ‘a country squire’. He remembers what a great environment it was for his own family to grow up in: always playmates to be found, other adults available if needed and spacious family quarters if privacy was required. The family had their own living room, dining room and kitchen on the first floor and the whole of the second floor was for their private use, though Astrid was surprised one day when she came out of her bedroom to find a boy’s mother waiting to give her an Easter egg. Ian and Astrid’s sons, Tom and Edward, loved living in the house. When they were very small Ian would spread his academic gown on the floor in a corner of his ground-floor study and Tom would curl up on it and go to sleep while Ian worked. The boys were adopted from Thailand and in the school holidays Bell House provided a wonderful venue for the reunions Ian and Astrid would hold with other families who had also adopted children from Thailand.

Matron would organise uniforms and every few weeks would arrange for a barber to set up a chair in one of the dorms and give every boy the same haircut: a short back and sides. She even cut the boys’ toenails in the 1970s. She gave flu jabs and dealt with minor ailments while the nurse and doctor at the Sanatorium dealt with more serious illnesses. Matron had a bedsit on the ground floor with a kitchen next door where she would prepare the boys snacks, hot drinks and treats like pancakes on Shrove Tuesday. No longer was a servant sent from the College to clean their shoes, the boys now cleaned their own. Prefects had use of ‘the library’ (now the Wissmann Room), to relax; they would also polish their army boots there. Danny McFarlane, a boarder in the 1980s, remembers many adventures at Bell House. Midnight feasts, pillow fights and once, when he was in the tutor’s dorm (now the Lucas Room) he and some fellow boarders climbed out of the window onto the top of the kitchen bay, to meet friends in Dulwich Village. At the end of the evening there was a string to pull to tell the boys still in bed that they needed to get back in. He remembers watching ‘The Young Ones’ in the TV room, just off the common room (what is now the chair store).

In 1992 the College briefly considered leasing Bell House for the new kindergarten (now Dulwich College Kindergarten School or DUCKS) before the Dulwich Estate sold the house into private hands. Andrew Cullen and his family lived here until 2016 when it was bought by the Hanton Educational Trust.

Housemaster David Verdon Knight in his study. Source: Cheryl Spray

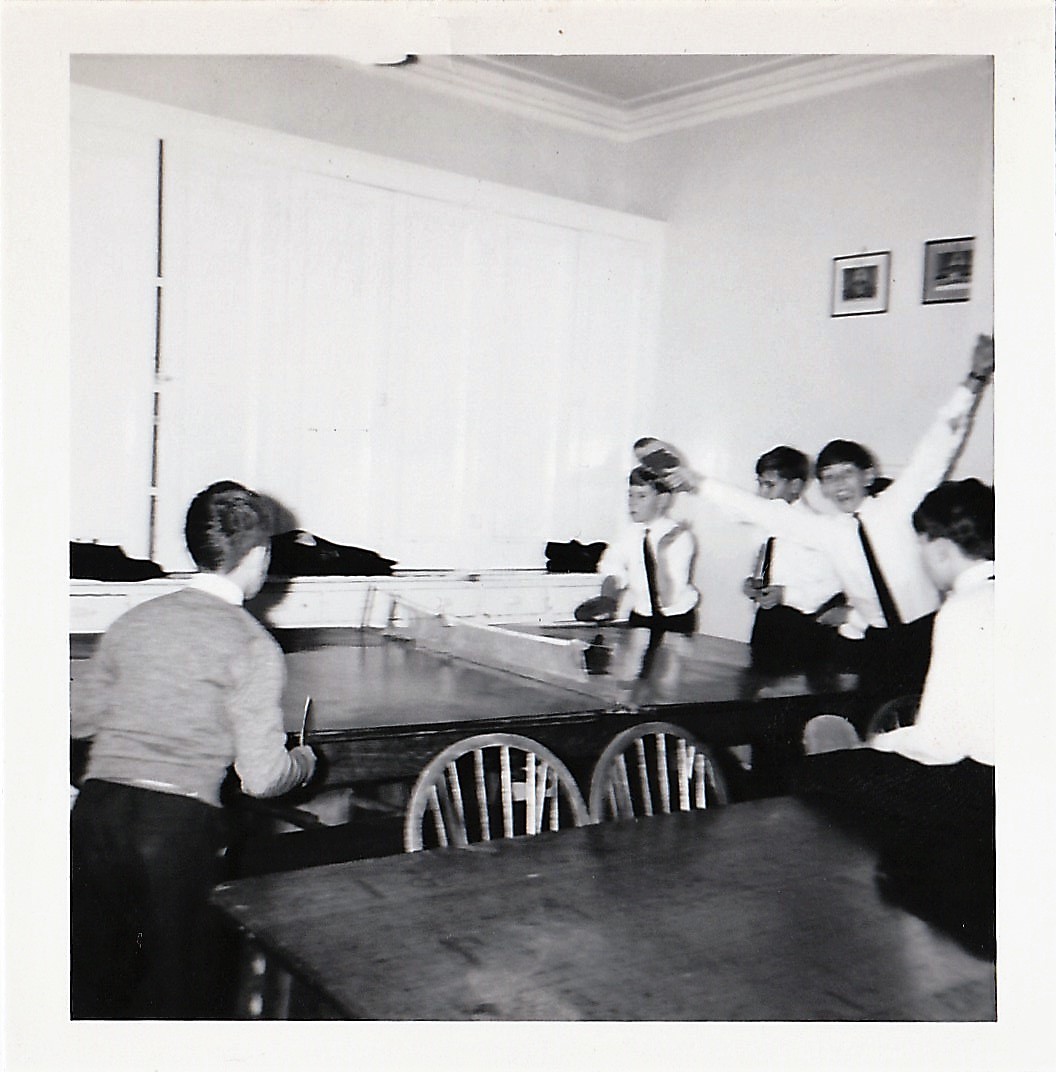

Boarders playing table tennis, 1950s. Source: Cheryl Spray

The Queen and Prince Philip driving through Dulwich, 1953. Source: Michael Palmer

View from a rear window showing the garden and Frank Dixon Close. Source: Cheryl Spray

View from front window. Source: Cheryl Spray

Housemaster David Knight's children: Cheryl at the door with Domino, Roger on the roof. Source: Cheryl Spray

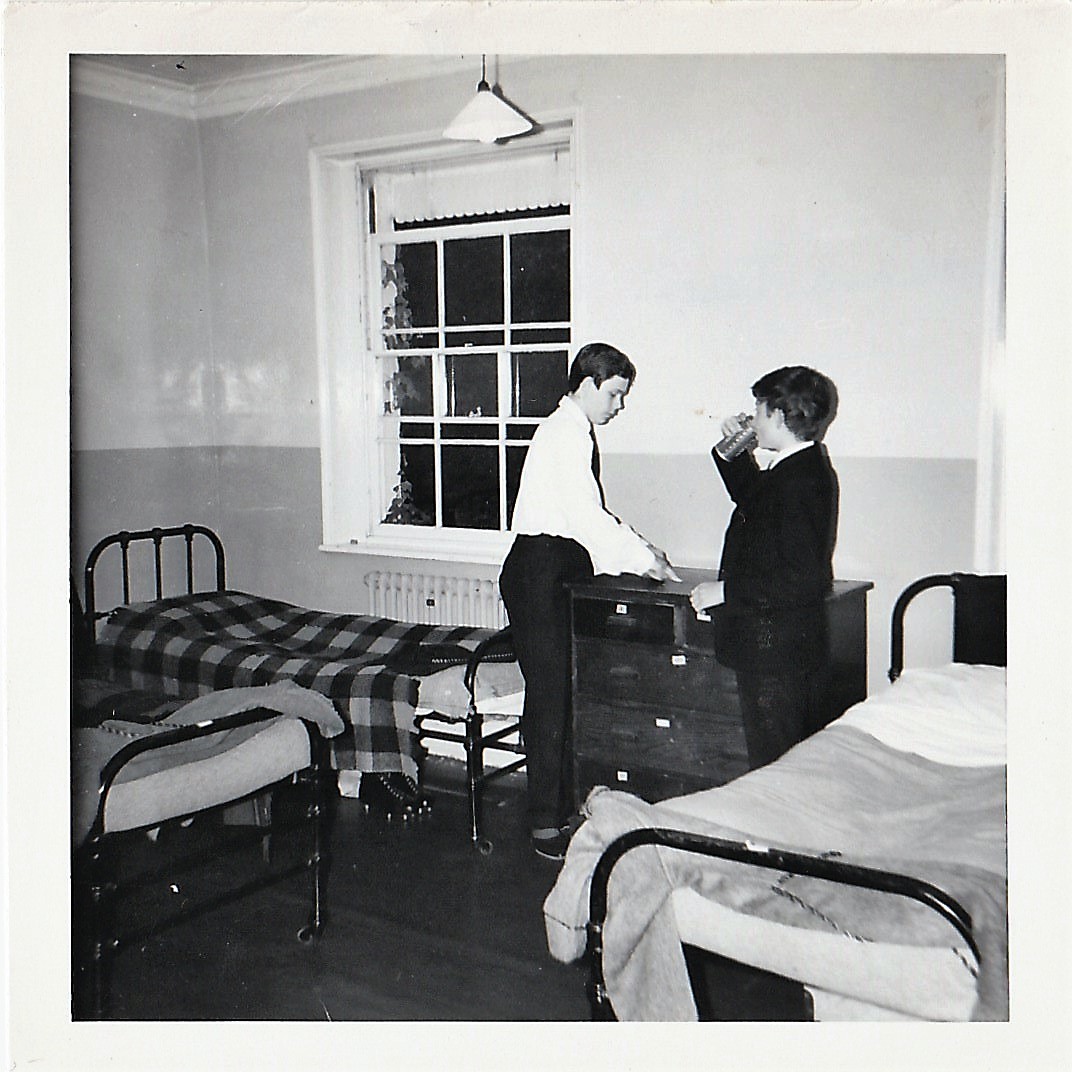

Tutor's dorm. 1967. Source: Cheryl Spray

Boys in the back garden. Source: Tony Powell

Boys playing snooker. Source: Cheryl Spray

Geoff Waterworth, house tutor. Source: Tony Powell

Domino, Bell House dog. Source Tony Powell

Patricia Knight mowing the lawn. Source: Cheryl Spray

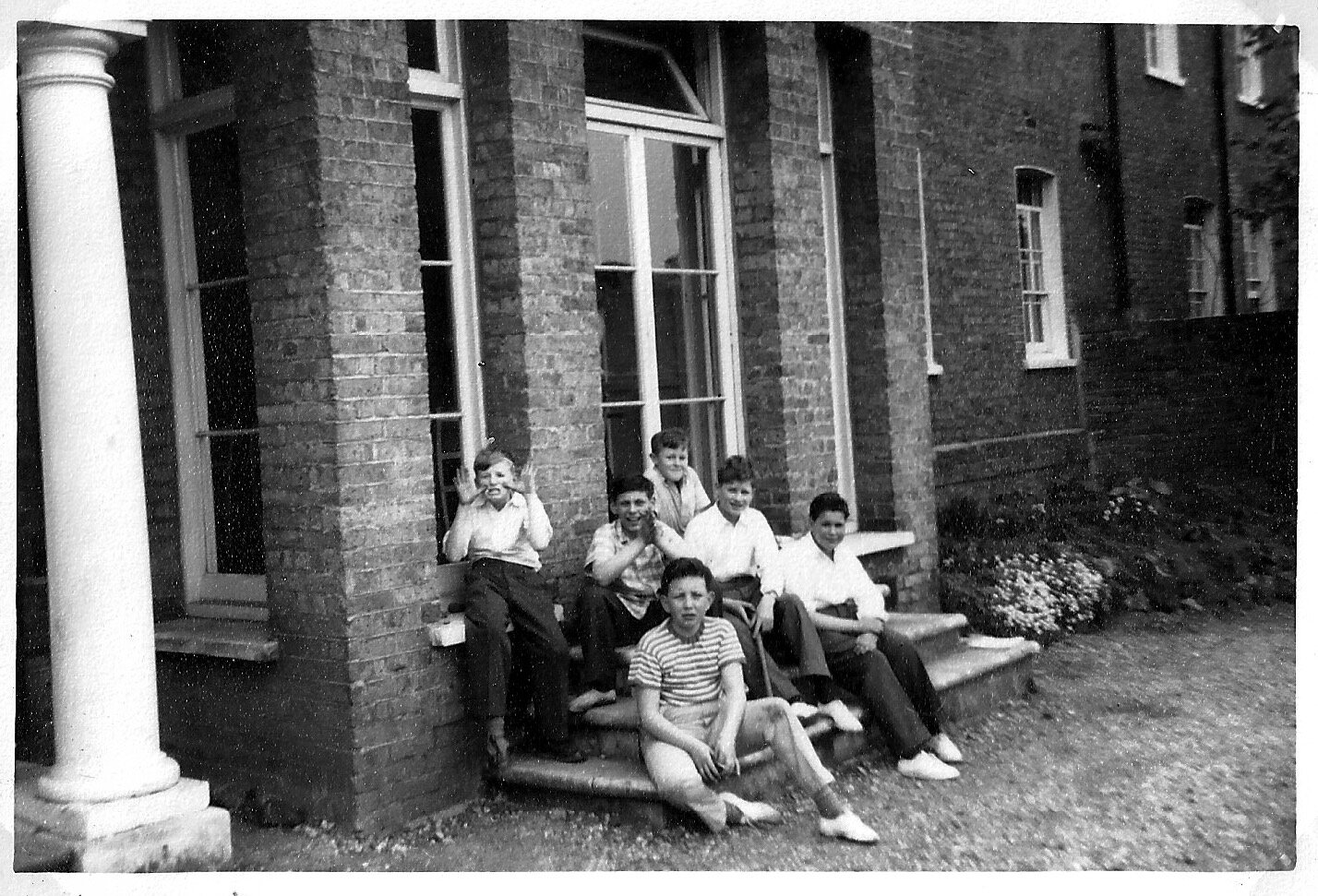

Boys outside the Bell House common room. Source Tony Powell

Boarders and Knight family in the garden. Source: Cheryl Spray

View from Frank Dixon Close, late 1950s. Source: Cheryl Spray

Bell House monitors in the kitchen garden, 1958. Source: Cheryl Spray

Tony Powell with the Tyro cup for shooting. Source Tony Powell

View of the pond dug for the Queen's coronation in 1953. Source: Cheryl Spray

Patricia Knight beside the pond. Source Cheryl Spray

Patricia Knight with Domino. Source: Cheryl Spray

Tutor’s dorm, 1967. Source: Cheryl Spray

Bell House Christmas card, c. 1967. Course John Tudor

Lines or ‘Pages’, written out as a punishment. Source: John Tudor

Graffiti in the cellar

Boarder in tutor's dorm, c.1983

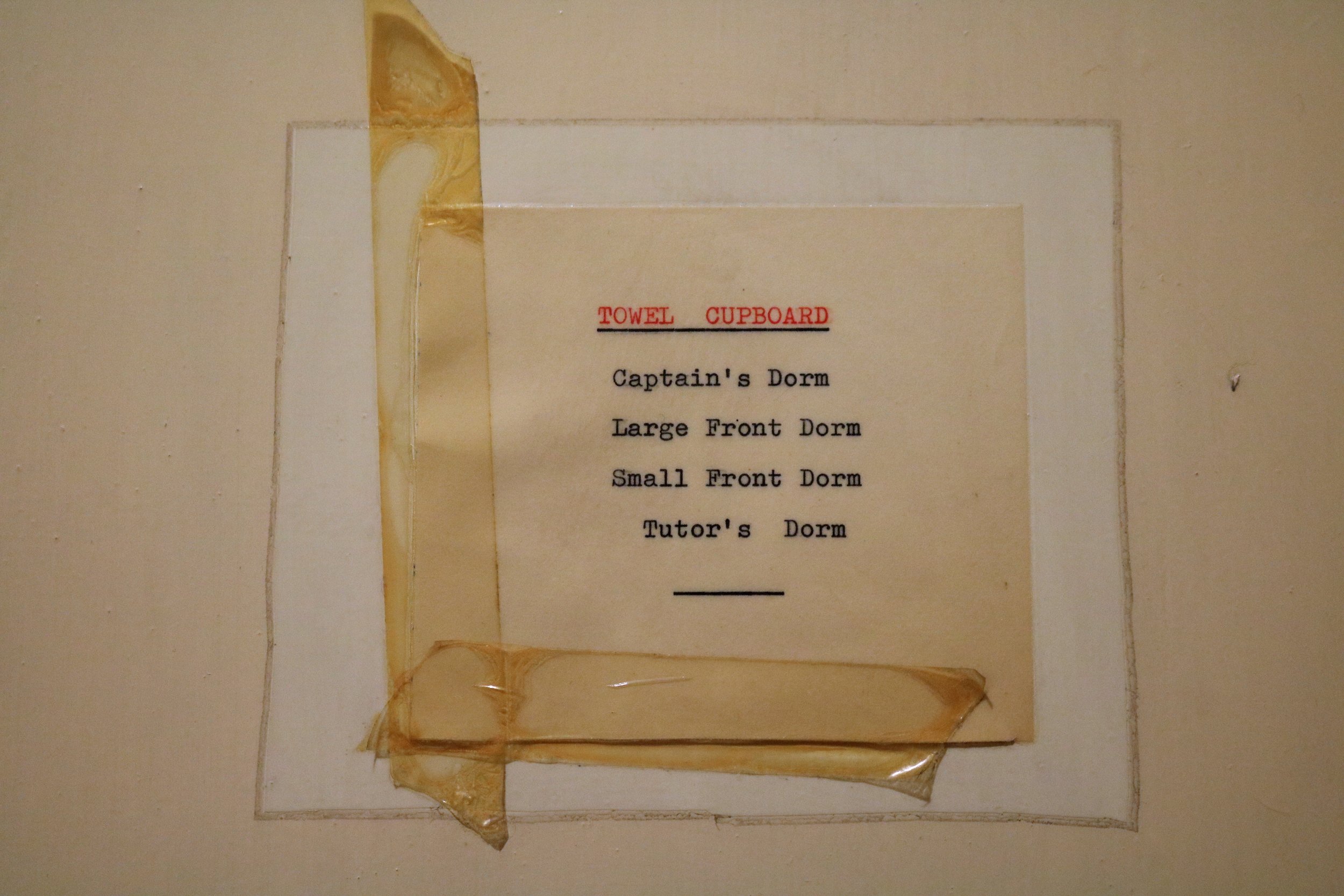

Label from the linen cupboard

Boarder outside common room, c. 1983

Last ever bath rota from Bell House

A proud boarder with his Bell House group photo

Trustee Fabienne Hanton with former residents Roger Knight and Cheryl Spray