THE WIDDOWSON FAMILY

George Widdowson was a celebrated silversmith and jeweller who made medals for the British Empire and swords for the army and navy.

In October 1852 Elizabeth Withington sold her lease of Bell House to George Widdowson. He had been born in Lincoln on 25 August 1804 the son of William and Elizabeth; his father kept the Rein Deer Inn in Lincoln.

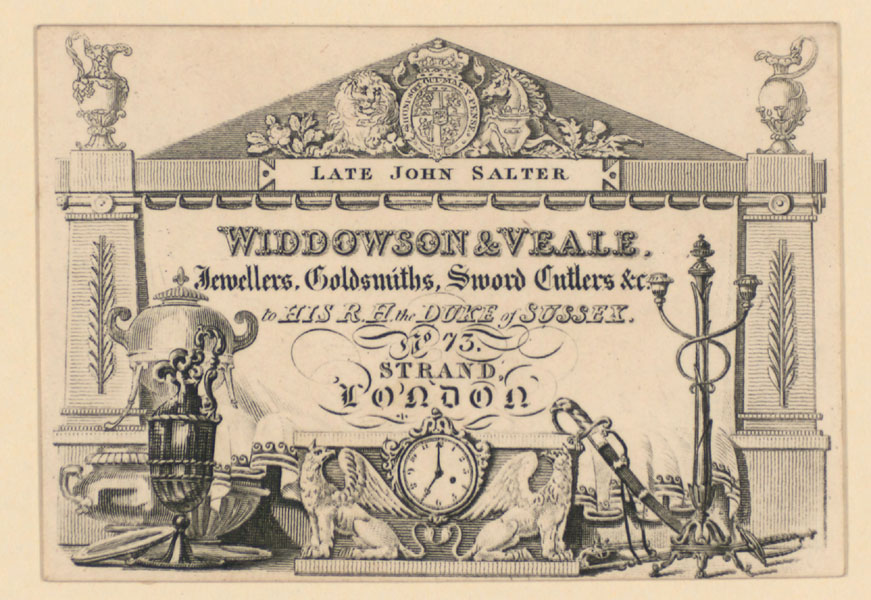

George was a silversmith and goldsmith, though a retailer rather than a craftsman and by the age of 28 he had taken over his uncle’s London shop on the Strand. His uncle, John Salter, had been a close friend of Lord Nelson’s daughter, Horatia, and was godfather to one of her children. The shop was very successful and John Salter had supplied Nelson with many pieces of jewellery, including mourning rings.

Widdowson developed the shop into the highly fashionable Widdowson & Veale at No. 73 Strand, on the corner of Adam Street and opposite the Adelphi. Widdowson had a real eye for marketing. He once had a detailed newspaper article dedicated to his proposal to make a copy of Aeneas’ shield, as described in Virgil’s Aeneid. There is no evidence the shield was ever made though it did get good publicity.

The company made swords and other weapons for the British army and navy, orders and decorations for the British court and were goldsmiths and jewellers to the court of Spain. In 1842 on the christening of Queen Victoria’s eldest son (later King Edward VII), Widdowson’s eye for publicity meant that the firm gave a christening gift of ‘an immense silver coronet supporting the Prince of Wales feathers.’ ‘Of a large size’, added the Times report, in case the splendour of the gift had not been clear.

In 1844, George was 40 and his business was doing well, as was the economy as a whole. The firm were able to advertise for apprentices, asking for a premium of £100. On 11 February 1847 George married Eliza Duffield (nee Boville), the daughter of a Putney wine merchant who had been living in Gibraltar but returned when her first husband, John Duffield, died. George and Eliza were middle-aged when they married and did not have children.

The Great Exhibition, Crystal Palace

In 1851 the population of Dulwich was 1,632. Business was booming for George Widdowson and at the 1851 Crystal Palace Great Exhibition, Widdowson & Veale exhibited (at their own expense) a large silver ‘plateau’ with candelabra, dessert stands, dishes, flagons, jugs, coffee pots, teapots, jewellery and an equestrian statue of Wellington. At the 1862 exhibition the following year they produced a similarly lavish display. George must have been delighted when the Crystal Palace was relocated to Sydenham, where it was almost visible from his front door at Bell House.

Taxi drivers not going south of the river

In March 1859, George gave evidence in the case of the ‘saucy cabman’, when Edward Gilbert, a cabdriver, was charged with ‘extraordinary and insolent conduct’. George had hired a cab in the Strand to take him and a lady to his house in Dulwich. On reaching Waterloo Road, the cabdriver said his horse was too tired and would not be able to do the journey and return to town; he begged his fare would take another cab and said he would charge him nothing for the journey so far. The court heard that ‘the appeal was so reasonable and the appearance of the horse indicating the truth of the driver’s statement, that George at once got out’. He went up to another Hansom cab on the stand but found the driver absent, so went to the next cab, which he found was actually driven by Edward Gilbert. George got in and was asked ‘Where to?’, he answered ‘Dulwich’ and was then pressed to say exactly where. He replied ‘the Bell House’. Gilbert asked what Widdowson was going to pay him for taking him there. On being told he would be paid the fare only, Gilbert refused, saying it was ‘beyond his distance’. George told him the distance did not exceed five miles and insisted upon being driven but Gilbert continued to refuse and ‘submitted him (witness) and the young lady to the gaze of the crowd that had assembled, and the consequence was that the lady was very much alarmed indeed’. Mr. Widdowson said that he had never encountered anything like the insolence of the defendant, and though it had cost him much trouble, he was determined on public grounds to have him punished. Other witnesses corroborated George’s statement. Gilbert was found guilty and the judge said the case was so scandalous that he would have sent the defendant to prison. However, it was his first offence and he had a large family to support, so instead fined him 40s, or 30 days imprisonment.

Charity

George was involved in charitable work. He was a steward of the Goldsmiths’ Benevolent Institution and supported them financially and his firm also made donations to the newly built Charing Cross hospital. George had an older brother, Joseph, living in London at this time but he was a less successful jeweller and set up shop at 100 Fleet St but in 1832 he went bankrupt. Eight years later he was confined to Bethlem Hospital, better known as Bedlam. There had been a Victorian boom in building institutions for those suffering from poverty (workhouses) or mental illness (asylums), though they were often lumped together. Over the century from 1800 the number of people housed in asylums rose from a few hundred to 100,000. At first these were peaceful places where it was believed mentally ill people could be cured by ‘moral treatment’ but this changed when it became widely believed that such people were ‘incurable’. Joseph Widdowson had suffered a fall which ‘caused confusion’ and, said his wife, meant he was ‘likely to set the house on fire’. He told Bethlem he ‘had plenty of money’ and indeed at the time inmates had to pay for their own care. While it might seem strange to us that George would have allowed his brother to be admitted to a place like Bedlam, there was little choice at the time and in fact Bethlem was a purpose-built state of the art institution, better than many. In any case, Joseph was not there long as he was discharged later that year into the care of another institution as he was suffering from ‘general paralysis of the insane’, an illness related to syphilis.

In 1859 George and Eliza made several trips to Brighton to stay at the Albemarle Hotel on Marine Parade, not just during the season, but in December too. It was fashionable to bathe in the sea as a cure for medical complaints and it’s possible that Eliza Widdowson was already suffering from the illness that led to her death.

Eliza died at Bell House in April 1861 aged 63, leaving George a widower. She was buried on 12 April 1861 in West Norwood Cemetery. Dulwich had now grown to house 1,723 residents but Bell House must have been a quiet place as George now lived there with just his unmarried sister Ann and his wife’s brother John Boville.

The three residents of Bell House employed a footman, coachman, cook, housemaid and lady’s maid. Footmen were often hired ‘by the foot’, that is the taller you were the more you were paid. Perhaps Bell House was too big and too full of memories as George did not stay long at Bell House after Eliza’s death. In 1863 he moved into the White House in Dulwich Village (where Japs Pre-Prep is now). George Widdowson died on 10 December 1872 aged 68. He is buried in West Norwood Cemetery in a Grade II listed tomb and he left around £30,000.

Widdowson’s executors auctioned off his effects in February 1873. As well as the household furniture, Wilkinson & Horne, the auctioneers, listed ‘1100 ounces of antique plate, plated articles, jewellery, a very elegant fine gold vase richly jewelled, antique watches and gold coins, Dresden, Sevres, Berlin, small other china ornaments, pictures, 100 volumes of books, 40 dozen of choice wines, 6¾ octave cottage pianoforte in ebonised case, elegant cabinets, ormolu and bronze candelabra, time pieces, carriage and dog-cart, valuable plants, cow, two stacks of capital hay, and out-door effects. Strangely, a year after he died an advert was placed in the Daily Telegraph: ‘FOUND: a large black bitch, name on collar George Widdowson Esq, Bell House, Dulwich’. The advert went on to say that the finder would give the dog to its owner on payment of ‘expenses’; if the dog was not claimed by 7 November it would be sold.

George Widdowson’s signature

George’s father’s pub the Rein Deer Inn, Lincoln

Nelson’s mourning ring, made by George Widdowson’s uncle

Widdowson & Veale trade card

Widdowson & Veale, 73 Strand

Widdowson & Veale, 73 Strand

Widdowson & Veale on the Strand

Order of the Bath, made by Widdowson & Veale

Widdowson & Veale sword

Silver plateau exhibited by Widdowson at the Crystal Palace. Bridgeman